Re- View #9:

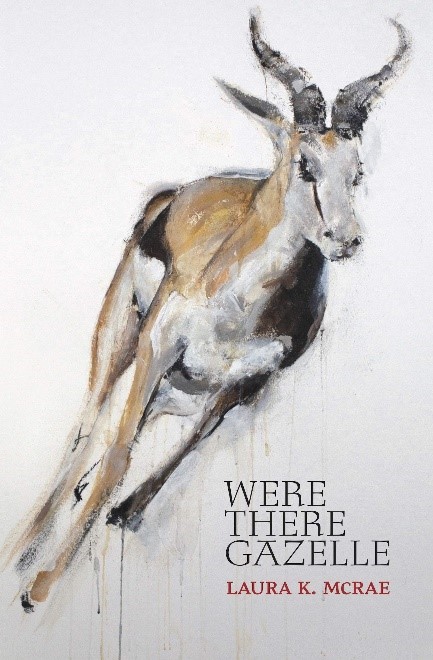

Were There Gazelle

Laura K. McRae, Pedlar Press, 2020

By Jami Macarty & Nicholas Hauck, Co-founders & Editors

Jami: Here we are, welcoming Re- View #9 to The Maynard Views Series! One of the notions behind this series is to bring forth books, authors, and publishers who may not receive as much attention as others for whatever variety of reasons having to do with timing, luck, and a host of other arbitrary factors concerning which books get noticed or don’t. I’ve hoped to consider a book by St. John’s publisher Pedlar Press for a while and am delighted the time is nigh. This time around, we’re talking about one book: Were There Gazelle by Laura K. McRae. After three previous reviews, each of which addressed two books, I’m revelling in unfettered wordcount and poised to focus our process on one book again.

Nick: There have been a few times with the three previous reviews about two books when we’ve felt as though there wasn’t enough space to say all we had to say. So, I’m with you; reading one book will change the conversation and allow us space to bounce these poems between us. Let’s go!

Jami: Let’s start at the beginning and, in a sense, judge this book by its cover. The title of McRae’s collection, Were There Gazelle, immediately captured my attention. That immediacy is owed to the dynamism inherent in title’s syntax and sonic qualities. My ears appreciate the rhyming consonance and assonance among the three words. Also intriguing are the title’s conceptual and conditional meanings.

Nick: The conditional, perhaps hypothetical, structure of the title caught my attention right away. In hindsight, it’s difficult for me to talk about what, if any, expectations the title encouraged; it does point to the speculative, the imaginary. The title also hints that this book might deal with the uncertainties of time, which it does mainly by working with the past. There are only a few moments where the future is projected.

Based in concepts, having to do with the effects of time on memory and other remainders—“in soft red earth”—the poems seem to seek the causal.

Jami: Along with the conditional and hypothetical, the poems contain inquiry: “Did a gazelle pause on tender hooves, / print the tiny half moons of her passing / / in soft red earth?” (“Were There Gazelle: Waiting,” 28). Based in concepts, having to do with the effects of time on memory and other remainders—“in soft red earth”—the poems seem to seek the causal. Aesthetically, the poems are predominantly lyrical. The conditional Were There Gazelle is a lyric expression. The meaning, too, which implies a bygone time, is a lyric, elegiac expression. Narrative often mixes in with lyric. Poems under the influence of narrative, default to use of prose conventions, such as the declarative: “I imagine…”; “I see…,” which are regularly deployed to advance the poems. Rather than balancing and varying the lyric, narrative threatens to subsume and washes out lyric compression and concision. An example of this, comes seven pages into the third section’s “Distributaries,” when a narrative about cars and films steals the poem:

Chargers gallop into battle, and Travolta

guns his engine under the Sixth Street bridge,

skirts the narrow

L.A. River ribbon and feeds his Mustang

as we fed our steeds, curries it with moleskin,

tools tires like hooves.

The Stanley steamer

charged on wood and water. Push a hose

over the side, hope you siphon

water, not the east Texas swamp, fuel it

like the old African Queen,

Bogart in the waist,

dry wood for a finicky engine. Now

we burn gasoline, smoke the same

grey-black

and pungent.

(“Distributaries,” 70)

After a few reads, I started to question whether there is some identity slippage between the speaker in the poems and (the) gazelle(s). Or, envy?

Nick: Right. The lyric expression dominates. I keep wondering about how this works with the title. After a few reads, I started to question whether there is some identity slippage between the speaker in the poems and (the) gazelle(s). Or, envy? The title suggests desire, too. Or, even longing. In a way, the identity play between human and animal is palpable in the different language aesthetics of the poems. Most of the time, narrative is used to talk about human-built spaces, cities, landmarks. When the natural landscape, gazelles, the birds (so many birds!), and other animals appear in the poems, language becomes lyrical, and sometimes verges on romanticizing. The poems’ language can’t escape the lyric, narrative, and descriptive.

Jami: Other than through narrative, the poems move and make meaning via image, privileging seeing, looking, and watching. Content is delivered in imagery and “hovers at the edge / of vision” (“Distributaries,” 72-3). On occasion there’s a surreal image, e.g.: “We cannot see the lines / in the hand of the lake” (“Bones of the Cathedral,” 11). By the way, I think this is Great Slave Lake, Northwest Territories; “Dettah Ice Road” tipped me off. More often though, the image is rendered photographically, even painterly. Sometimes the looking is framed, often by a window, canvas, or lens: the world seen converted to a still life. As I read, I had the sense of leafing through one of the poet’s old travel albums. The repetitive visual references seemed to flatten some of the poems. Indeed, two-dimensionality wore on me here and there.

Nick: The poems in the first section, “The Dead Are Dead,” feel especially like postcard scenes. Built landscapes are privileged. Even the titles read like labels in a photo album: “This is Fes,” “Village in Kerala,” “Atchafalaya Basin, Louisiana, May 1986.” And, there’s the camera taking the photos, which plays varying roles throughout the book. Sometimes “the camera [is] around her neck” (“Atchafalaya Basin, Louisiana, May 1986,” 29); then, “she is pleased to have the man take her picture” (“Encounter,” 30); then, first person lyric as photographer; “my face behind the camera” (“Ring of Brodgar, Orkney,” 39). In the book’s second section “It’s a Far Cry,” tourism is explicit: “buy a postcard, book of photos?” (53). There are witnesses and those being witnessed, and the photograph is framed, as device, and always leaves something out. Do gazelles take photographs?

The poems are verbal records of the photographic records of the poet’s travels to urban centers.

Jami: I want to quibble with you—and the poet—on the use/suggestion of “landscape.” “Landscape” speaks to natural settings at a human interface. The settings of these poems, and what is seen in those settings is predominantly situated in the urban. The poems are verbal records of the photographic records of the poet’s travels to urban centers—Tangiers, Fes, Istanbul, Beijing, New Orleans, Toronto, etc.—and her viewings of man-made structures in these cities. These travelled-to cities suggest form and formal concerns. The photographic qualities embedded in the work points to the ekphrastic form. Sometimes the poems make explicit their ekphrasis, as in the poem, “I See China,” a response to JMW Turner’s painting, “The Blue Rigi, Sunrise, 1942”: “The Blue Rigi is in Switzerland, but the boat says China” (38). The long poem that forms the book’s third section, “Distributaries,” refers to several painters:

A skull lies beside the road

a Georgia O'Keefe

the colour of the concrete slab

where the laugh house once stood,

round, littered with desiccated fruit,

the colour of the calla lilies

in that Diego Rivera nude.

I bought a replica

at Frida Kahlo's home in Mexico—the blue

walls, the garden, green-spangled, and the painted

woman

her back streaked olive, arms curved

(“Distributaries,” 71)

Curiously, the mentions of art and artists in this excerpt give the reader the paintings, though not their titles. The reader can’t know for sure to which works the poet’s referring. The poet uses the paintings as descriptors of colour. This descriptive usage makes a statement about representation and the way well-known paintings become part of mainstream culture, shedding distinction, the proper noun.

Nick: Further on in “Distributaries,” the desert sky is compared to “Van Gogh’s Starry Night,” (76), and then some pages later, “Matisse … / in Tangier, / … painted / / square, white buildings, / delphinium sky. Those canvases / never show the street” (“Distributaries,” 87). There are writers mentioned as well, idealizing Northern Africa as a haven of creativity: Hemmingway, Bowles, Burroughs, Stein, Wharton. These painters and writers are major, recognisable figures, almost tropes; it’s a Kahlo “replica.” It seems to me that these cultural landmarks are removed from the poet.

There’s the feeling of the poet removing the writers and artists from their personages—their proper noun designation—and transforming them into adjectives for the purposes of the poems.

Jami: Definitely, there’s removal. I think that quality references the past, the pleasures and pains of writing from memory. There’s something about the treatment of the writers and artists by McRae. There’s the feeling of the poet removing the writers and artists from their personages—their proper noun designation—and transforming them into adjectives for the purposes of the poems. Writing is acknowledged within the poems; often the poems are textually reflexive. You mentioned the writers who moved through Tangiers—how are you making sense of their presence? Which is foregrounded—Tangiers or the artists? The poem, “Evening in Toronto, August, 2013,” that marks the death of the great Irish poet, Seamus Heaney, has a more intimate, felt quality, marking the affect of loss.

Nick: The writers I mention are all referenced in the poem, “The Sun Casts No Shade,” because “it is always noon in Tangier.” Unlike some of the other cultural references in the book, in this poem, the writers’ presence is quotidian and the poem makes no mention of their craft: “Bowles […] shared a glass with Burroughs”; “Stein nursed a brandy and soda”; “Hemingway / tamps his pipe”; “Wharton sips her drink,” (23). I’m not sure what to make of their treatment in the poem. Maybe the traveller is simply seeing their ghosts, hanging out having a drink.

Jami: Speaking of shadowy forms, in other instances, the ekphrastic form ghosts the poems, as in this sentence from the long prose poem sequence, “It’s a Far Cry,” that defines the book’s second section: “The photograph is vibrant, but the green has faded,” (61). This reference appears on the seventeenth and final page of the poem, delaying the reader’s cognizance that photos are being looked at and also those photos’ whens and wheres. What seems most important is the colour of the photo and the recall it prompts.

Colour is everywhere in these poems, as are references to eyes and looking, as if there is an attempt to recreate the visual experience

Nick: Colour is everywhere in these poems, as are references to eyes and looking, as if there is an attempt to recreate the visual experience of the “honeyed light” (“Distributaries,” 78), the “iridescent, a black pearl” (“It’s a Far Cry,” 53), or the “green-mottled” (“Distributaries,” 81). It’s striking how vivid the palette is. The poet tries with seeing to do what seeing can’t do. There’s a line early in the first section: “if I could photograph time” (“How to Know When the Dead Are Dead,” 24) where we’re thrown into the hypothetical, wanting the image to do something it can’t: remember. The image can show, in wide spectra, but it can only be a prosthetic for memory, a replica of experience.

Jami: Notions of reproduction, replacement, and augmentation factor into the treatment of the numerous and varied birds that inhabit these poems. There's something odd about their treatment, though. Sometimes the actual birds appear: “donkeys carry cages of cocks,” (“How to Know When the Dead Are Dead,” 24). At other times, birds are descriptors—just as in the treatment of paintings/painters—the part of speech changes from proper noun to adjective: “We fry pancakes as an owl of fog / ghosts across the gloaming,” (“Bones of the Cathedral, 12). Things are not themselves but descriptors, qualifiers of other things.

Nick: Writers, painters, birds, colours—they all seem to carry out linguistic functions other than what they are.

Jami: A similar treatment of flowers, and of precious and semiprecious gemstones occurs to describe colour:

The mountain’s greens:

emerald, malachite.

Not the sea’s lucent jade,

bluing the pitch-dark depths, but clear—

like your eyes.

(“Bones of the Cathedral,” 13)

and

on a rooftop in Tangier’s kasbah,

you can look across that cyan stretch

streaked with sapphire and the pale

wash of hyacinths

(“Distributaries,” 86)

For another example, in the poem, “I Listen to Istanbul,” there’s a “hyacinth-veined floor” (20). While gemstones are used only as descriptors of color, flowers and food sometimes also appear as themselves, as nouns: “a single gilded iris emerges from the water” in the poem, “Atchafalaya Basin, Louisiana, May 1986,” (29), and in “The Sun Casts No Shade,” “the spirits … buy olives, greens from / the Berber women,” (23). This treatment of flowers, food, and gems evokes painterly qualities: the colour of things matters more than the things.

Nick: Is this memory’s eye? Having to forgo the tactile and audible makings of past experiences, the only recourse is to the visual, layered on thick. Light, shadows, and darkness are important in the poems as well. Often, these moments set the stage, as if for a painting or photograph, whether “silhouetted by candlelight” (“Evening in Toronto, August, 2013,” 25), or when “sun whites the alleyway” (“This is Fes,” 27), or “the headlamps / gleam” (“Distributaries,” 64). In “I Listen to Istanbul,” there are moments where the visual seems to determine other senses; even though “I listen to Istanbul, intent, eyes closed” (20), the metaphors in the poem are predominantly visual. In these poems, I see the image/photograph blurring representation and fiction into a faded image.

In a weird way, the photograph itself, that artifact, isn’t what matters, just as the paintings referred to aren’t focal. Instead, each is used to describe or to remember.

Jami: In a weird way, the photograph itself, that artifact, isn’t what matters, just as the paintings referred to aren’t focal. Instead, each is used to describe or to remember. Memory matters: the memory of the photographer, the one seeing. Given that much of the book takes place in the past or in remembering the past, these are poems unmistakably about reality and illusion: “It’s a far cry from the Delhi of my dreams” (“It’s a Far Cry,” 50). What is remembered, what made an impression, what has left its “mark— / a scratch at the heart, … / / like a bootprint in tundra,” as the Elena Johnson epigraph to the book expresses, is what matters.

Nick: I guess then these poems are talking about the way memory marks us, being marked by time and experience, the traces fading, and how remembering needs support and is never quite right. I get a sense that memory here is being attributed to humans and held up against the animal world. I’m uneasy about this distinction. Marking, tracing, the hoof print, is a form of memory too. There’s a back and forth between the human (fabricated) world leaving its trace and the natural world’s marks. In a way these poems speak to the Anthropocene, but would you go as far and say there’s an ecopoetics?

Jami: The Johnson epigraph fused with the title in my mind to form the possibility for an ecopoetics. However, if the book were written out of an ecopoetics, I think the treatment of the natural world in language would be quite different. Following from my remarks about proper nouns and adjectives, there’d be more proper nouns combined with uses of the literal and actual in the poems. The gazelle, when they appear, don’t always have the feeling of actual gazelle found in Africa and Asia. If they are, why are they not more specifically named and located? On the book’s cover is a Thompson’s gazelle; the “tommie” roams the savannahs of East Africa, the Serengeti of Kenya and Tanzania. In the series of poems bearing the title “Were There Gazelle,” I don’t have a strong sense of place, whether the Serengeti or another locale. Actual place isn’t what’s foregrounded. The gazelle in the book have mythic or dreamlike qualities: “a twilight / mirage,” (“Were There Gazelle: Delta,” 41).

I don’t see the gazelles as being literal.

Nick: I don’t see the gazelles as being literal, were they literal, that would be a different collection of poems, maybe a full-on ecopoetics. “Were There Gazelle: Sacrifice” opens with human flight when “An aircraft comes to rest on the stony perimeter,” and closes with a gazelle, a “White streak in the expanding distance” (21). Between the straightforward description of flying and the final line, I think the move toward figural language says a lot about how these poems talk about the natural world.

Jami: More than the literal, the poet relies on the figurative, and I suppose that makes sense given the temporality of the poems and from the distance they evoke. There is something about the distance of actual travel and the proximity of photograph playing out: “If I could photograph time, / I would capture this rooftop moment / / when the eighth century meets the twenty-first,” (“How to Know When the Dead Are Dead,” 24). This highlights the challenges of remembering, even with photographs. I’m thinking, too, of how impressions/marks amount to memories. The impressions or marks that a place leaves on our brains—that is what we refer to as memory. With that, the gazelle and other animals in the poems have the feeling of an elegiac device—not of the loss of habitat for gazelle or ecological concerns for other species, but for human life and memory: “There is no shelter in folklore” (“Were There Gazelle,” 99).

Nick: A few poems speak directly to family heritage, past generations, the deceased: “Your grandfather lies in Macedonia / under a grassy slope” (“Bones of the Cathedral,” 15) and to how monument and memory do not endure:

They lost track of his parents, mowed

down those wood crosses. My father says

he remembers them

though he could not

read the names. There’s a space

beside my mother, space

on her stone for Father's name.

(“Distributaries,”80-81).

Poems that mention family are scattered and fragmentary, mirroring the disconnect caused by loss, but is there mourning? Grief? How do these poems fit into the larger thematic of the collection?

At first, I wondered if the extensive travel within the poems formed a pilgrimage to the old country, motivated by familial ties.

Jami: At first, I wondered if the extensive travel within the poems formed a pilgrimage to the old country, motivated by familial ties: “Maunder between stones—aunt, / great-uncle, great-great-grandmother,” (“Bones of the Cathedral,” 15). In this opening poem are we in the Sedlec Ossuary, aka the Bone Cathedral in the Czech Republic? With each section of the poem, the setting seems to shift. At any rate, in these lines, travel seems purposeful, connected to family. If the travel in other poems is based in familial connections, the poet doesn’t cue the reader to that fact. So, mostly, travel is for travel's sake and not necessarily with any goal other than to see a place—the visual, again.

Nick: Yeah, I’m with you, and these movements all leave visual traces too. But humans don’t leave the same marks as gazelles, for whom there is “no vantage point,” (“Were There Gazelle: Sacrifice,” 21). Maybe the poet wants to leave traces like gazelles, so she writes as a way of tracing or marking instead. There are many birds and other animals in the poems, but, ultimately what the speaker knows best is the human world and its imprints, which may last, but knowledge won’t: “In the end, we are unmoored from / all we know,” (“Bones of the Cathedral,” 19).

Jami: Right, what’s foregrounded in these poems is the humancentric, human travel/movement, and the marks humans make to announce their presence, ownership, departure, death: “the marker crumbles,” (“Bones of the Cathedral,” 15). Memorialization of travel forms the spine of the collection. I keep thinking of that national park admonition: “Take nothing but pictures, leave nothing but footprints, kill nothing but time.” Photographs/y and images of markings, made by human and animal foot- and handprints recur throughout the collection: “The bones of the cathedral are vanished, / only hooves and nails, hair, remain,” (“Bones of the Cathedral,” 19). This is perhaps a poet who “takes” the “footprints.” Or, wants to make some! These poems connect how humans leave their mark on places and how places leave their mark on humans.

The visual descriptions work along with the theme of marking/being marked.

Nick: The visual descriptions work along with the theme of marking/being marked. The built landscapes we “see” are the markings of civilisation, but the speaker is also marking by describing. The poems are marks, too. They are the imprint of the world onto the speaker. Like an image burned into memory then projected onto the page, seeing and imagining collapse into each other in these poems. Sometimes, the imaginary is the only trace, as when “Our feet / make no mark / / on that floor” (“Distributaries,” 84).

Jami: The seeing makes a lasting impression. The poems are a lasting impression of a lasting impression. Footprints speak on various levels to effect and impression, to both impact and form. Another form comes to mind: travelogue. The poems share qualities with travelogues and feel like they were begun during travel or that a travelogue was excerpted in the making of the poems. The travelogue form speaks to the narrative and linearity within the poems.

Nick: Yeah! I think this linear directness works with the visual abundance, the sequential images. The urban scenes that command the poems are vivid and imaged, and this reaches for tactility. I keep thinking about the last line of the book where what’s left are “a few shining pebbles / to bruise our feet,” (“Were There Gazelle,” 99). Is this saying nature will always leave the last mark (on us)? Along with the human and the natural, there are names of deities and religious figures in the poems: Moses, Shiva, Hephaestus, Thor, Nandi, among others. They reference various faiths and mythologies and, like the writers in Tangiers, are almost made commonplace, profaned to the everyday: “Ragnarok hovers at the edge” (“Distributaries,” 72). This suggests the time of the deities is coming to an end. This is one of the few instances of futurity, hinting at a new world, whereas most of the other poems deal with worlds and places once visited.

Jami: In the book’s second section’s long prose poem sequence, “It’s a Far Cry,” which takes place in India, the travelogue as a compositional mode dominates. Travel is being privileged, and of course, traveling is embarked upon from privilege. At times in this poem, there is a self-consciousness or contrived affect. Maybe this points to the decorative and descriptive way the visual is used. At the level of language, the idiom, “it’s a far cry” was originally used to establish contrast and therefore takes the preposition “from,” as in, this is “a far cry from” that. In her poem, McRae toggles back and forth between the usage of the prepositions “from” and “to.” This has the effect of changing the idiom to establish distance traveled, both actual and in recall.

Nick: I struggled with this second section. The poem lost me in its travels; the travelling lost my attention. I even began to question its place within the book and wondered if it had a previous, standalone appearance in print. When I read the “Acknowledgements,” I learned that it was the third section, “Distributaries,” that was published previously as a chapbook. Funny enough, I feel that this section works well with the other two to rework and recirculate similar themes that attempt to recreate experience, observed from different poetic angles.

The major metropolitan areas being described are noisy and yet we barely hear anything. Inexplicably, it’s as if the world’s on mute.

Jami: I see a lot of beauty in the poems, but for me the observing doesn’t translate often or surely enough into feeling, experiencing. That raises a question about sound—the music of language, the sounds of nature, and of man and machinery. Where’s the sound of these places and in the language used to write about them? The major metropolitan areas being described are noisy and yet we barely hear anything. Inexplicably, it’s as if the world’s on mute. Perhaps that speaks to how memory visually unfolds in the poems. More than from an auditory imperative, the poems come forth via the soundless visual imperative. Then again, we remember sounds, too. Maybe this reader is simply too far off on one edge of the auditory spectrum?

Nick: Thanks for bringing music and sound into the conversation. When I first saw the title of the fourth section “Coda,” my thoughts went to music, although a coda is also a literary device. Then I noticed that there is little reference to music—that’s why the Eagles’ song stands out—and language rarely addresses sound. From there, I wondered, what is the sound of a gazelle? My own biases equate swift movement and silence to these animals. We see them in a flash, and that means we see more of the landscape. Do we hear them? In a way the poems silence me, as reader, too; I feel as though I’m being carried along “A muted breeze,” (“It’s a Far Cry,” 59) accompanied by an abundance of visual stimuli.

Certainly, language is musically alive with alliteration and onomatopoeia in these examples. So, why/how do my ears miss these sounds in the poems?

Jami: Is this silencing because of how often the reader’s shown? Maybe it’s the effect of capturing. Photos capture. So, the effect on the reader of viewing in the poems captures. There isn’t a lot of room for the reader to be in the auditory and kinesthetic experience of the poems. Of course, as soon as I say that, the poems remind and assert: “chatter of monkeys,” (“Village in Kerala,” 22) “clatter / of cutlery,” and “warble / of water,” (“Evening in Toronto, August, 2013,” 25). Certainly, language is musically alive with alliteration and onomatopoeia in these examples. So, why/how do my ears miss these sounds in the poems? I think it’s because of the usage of the prepositional phrases; they have the effect of making an image—a thing, rather than an action, or a noun instead of a verb. Often the visual effect is made more explicit: “clot of traffic,” (“Monastery, Sinaia, Romania,” 33) and “bubbles of laughter,” (“A Fox, a Dog in the Mist,” 36). These are also two examples of synesthesia. In the poem, “Were There Gazelle: Sacrifice,” sound is an action: “On my radio, / the bridge of “Hotel California,”” (21). The way sound is set up here has me singing with the poem. The enacting possibilities of language fascinate.

Nick: Right! Even in rare moments where the sound of a city is mentioned, like “the low drone of Fes, the ululating wail of Istanbul” (“It’s a Far Cry,” 46), the overall effect remains visual. Here, the descriptions of the sounds of Fes and Istanbul feel physical, not audible.

Jami: In these poems, there’s a lot of water—ice, fog, lake, sea—and, the fiery counterparts—flame and smoke—also the territory of the lyric.

Nick: Two water scenes that caught my attention involve tides. In one, a gazelle is spotted on a “scrubby sickle between sea / / and sea,” (“Were There Gazelle: No Chances,” 35). Why “No Chances”? Because this is an island? Cut off by “only moon and tide” (35)? In the first-person narrative poem, “Village at Birsay,” tide also isolates, but this time it cuts off the human world where “Norsemen worked” and “women carded wool and wove” (40). Tides also have a rhythmic erasure; they endure and return, but the traces do not.

Jami: Four of the five poems bearing the title, “Were There Gazelle,” are presented with a colon followed by qualifier: “Sacrifice,” “Waiting,” “No Chances,” “Delta.” The qualifiers make me ask: What/who is sacrificed? Who is waiting, and for what? Why are there no chances? I don’t know. Are the perils of life as a gazelle being compared to those of a poet, a woman poet? I only have more questions. Maybe the poem, “A Fox, a Dog in the Mist” can help. In the opening of this poem, “Anger is a fox curled in the cave of your chest,” but by the end of the poem, “There is no Fox. Just a cave of anger / and a distant dog in the mist,” (36). Is the gazelle—it’s not clear to me there is more than one—representative of an emotion, like anger, and if so, what is that emotion?

Nick: I want to get to the Coda, as one does. The only poem in this final section has the same title as the book and begins with the explicitly lyric: “Sweep of my hair, wide expanse of savanna, a gazelle,” (“Were There Gazelle,” 99). The poem is recapitulative in the sense that memory and time are addressed, but now with a view toward the future. There’s also (finally) an erasure of the anthropocentric when “these moments scour our passage” (99). I still don’t know what “these moments” are. Are they “a gazelle, / neck long, legs extended / / in flight as grass surges,” (99)?

Jami: With the coda, the concluding statement seems to render the death of the gazelle and what it represented:

There is no shelter in folklore,

and we taste what is to come

in what once was. These moments scour our passage,

clear it of debris—of our human

discourse and rot—leave a few shining pebbles

to bruise our feet.

(“Were There Gazelle,” 99)