Inter-

Otoniya Juliane Okot Bitek

On Practice:

Do you write at the same time every day, in the same place? How would you describe your writing practice/s?

Nope. Never.

My writing practice is to listen, jot down notes and listen some more.

I don’t have a particular writing space, although I have access to only one desk at our place. Mostly, my desk is full of paper and books and notes about books and notes and stuff that others want from me, or are paying me for. Therefore, my desk is not the place to sit and have a practice.

I guess I don’t have a practice, if practice is regular or bound to a particular space. What the hell.

Maybe I’m not even a writer, much less a poet. How can I be, if I don’t have a writing practice/s?

What do you do if you get stuck while writing a poem?

I don’t get stuck writing a poem. It gets stuck coming out. So I grease it and wait.

Sometimes it makes its way out and sometimes it doesn’t.

No point rushing a poem. When it’s ready, it comes.

Sometimes, what looks like a poem is the beginning of another idea but resembles a poem in the moment.

I don’t worry about getting stuck because I’ve convinced myself that it’s not ready and when it’s ready, it will come.

I also have piles and piles (just kidding, but more than I need) of poems that I forced out that are terrible bits of existence.

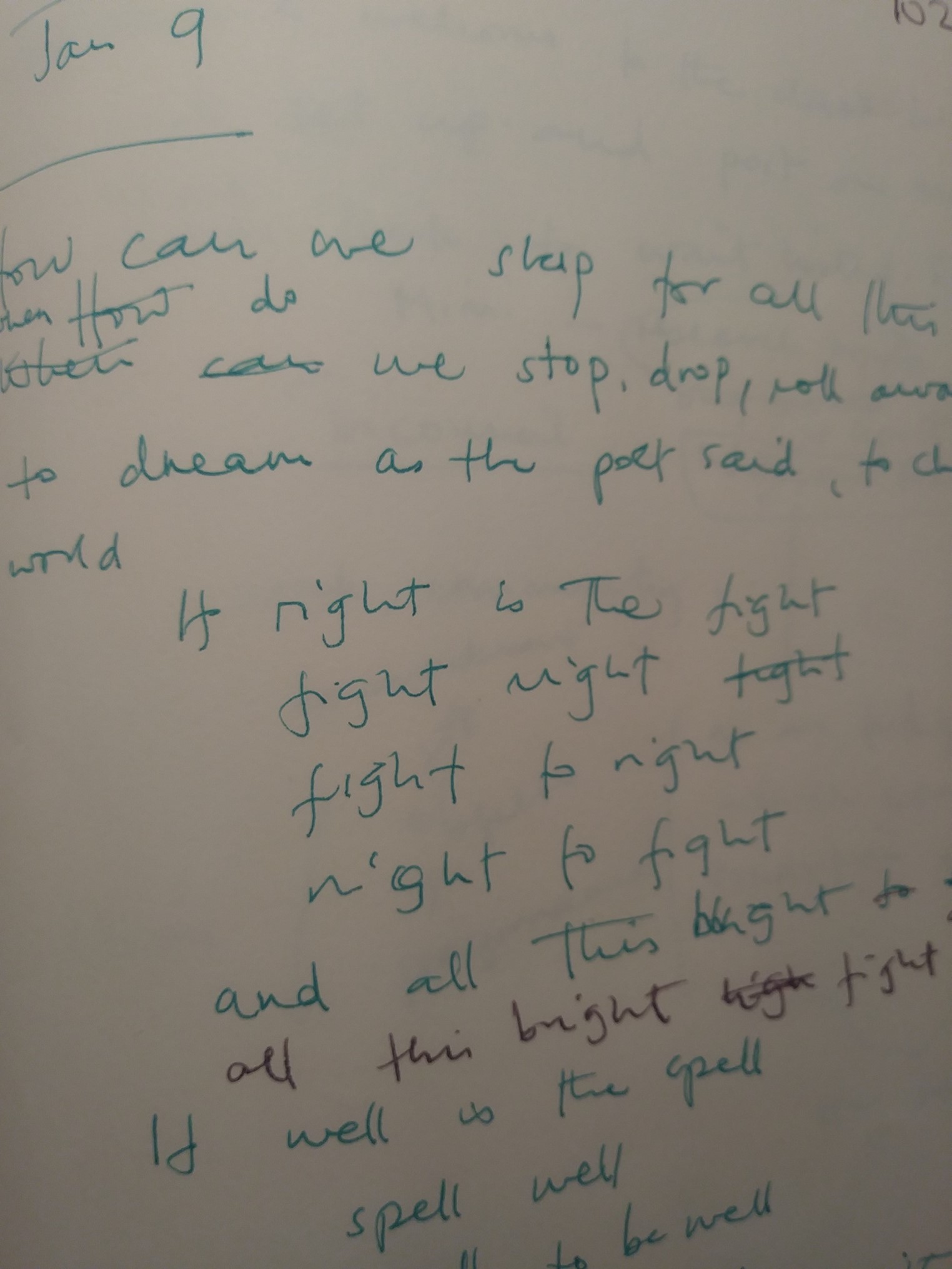

Take a photograph of a page from your notebook or a screenshot of an electronic file of a poem you have been recently writing or revising.

On Poetry:

Is there something you once believed about poetry that you no longer hold true? What changed?

I used to think that art and poetry contained the truth.

Now I know that any art or poem can be defined by the political present and that environment often has no space to imagine all of us. Therefore, it cannot tell the truth.

What can/does poetry change?

Poetry can change the rhythm of the moment, get us to slow down, or pick up the pace of life.

Is there something you now think you know about poetry that you wish you’d known a decade ago?

I wish I knew that poetry was like the playground from our childhood days.

On Influence & Inspiration:

What books are on your night stand, the back of the toilet, your desk?

Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward

Inventory by Dionne Brand

Just Us: An American Conversation by Claudia Rankine

The 2021 Ikea catalogue

Which writer/s do you (re)read the most? What does the writing do for you upon return?

Christina Sharpe

Toni Morrison

Dionne Brand

I re-read them to sharpen the knife.

Among the poets you most admire, who has influenced you the least? Why have you not been influenced by his/her work?

I have not admired a poet whose work hasn’t influenced me.

Describe a moment from your life when you've been overcome by how beautiful something is.

The glorious feel of my daughter’s hair as I plait it.

On Teaching:

How would you describe poetry to a four-year-old? To the non-literary family ancestor you imagine as a great source of who you are?

Why would I describe poetry to a four-year old?

I’d sing it with them and then tell them that any fun way of speaking or singing is a poem.

What characteristics does your ideal poem possess?

Rhythm

Do you teach poetry? If so, what are you trying to teach through poetry? What has poetry taught you?

Yes.

How to resist; how to tell a story.

How to resist; how to tell a story in my own way; how to break established rules of writing.

On Publishing & Themes Present/Future:

How has publishing your poems changed your writing practice, process, and product?

Publishing has broadened my mind about my relation to the poem—it has meaning to the reader that is, more often than not, nothing to do with me.

I’m more confident of the fact of myself as an observer and transcriber of experiences than I am as a creative person.

Is there a poem you've always wanted to write but haven’t? If so, why are you waiting?

The long poem.

I don’t have the patience for it.

What subjects, themes, forms, aesthetics, etc. do/will you explore in your work?

Un/settlement, diaspora, identity.

On Oranges:

Oranges or apples? Why?

Oranges.

I’m familiar with far more kinds of oranges than I am with apples.

Also, oranges are much kinder than apples. They’re just better people.

About the Poet

Otoniya Juliane Okot Bitek is the author of 100 Days (University of Alberta Press, 2016) and two chapbooks: Gauntlet (Nomados Literary Publishers, 2019) and Sublime: Lost Words (The Elephants 2018). Otoniya is the 2020 SFU Writer-in-Residence and 2021 Shadbolt Fellow at Simon Fraser University. She lives on the lands of the Musqueam, the Squamish, and the Tsleil-Waututh peoples in British Columbia.

Inter-

Nathan Curnow

On Practice:

Do you write at the same time every day, in the same place? How would you describe your writing practice/s?

Not at the same time, but always out in my backyard office where the sounds of the house can’t reach me.

I’ve never had a set routine, life offers too many interruptions for that, but a writing practice isn’t just about tapping away at the keyboard, it’s the whole life you live.

Writing gives me reason to be attentive, which also means I can often vague out around others.

What do you do if you get stuck while writing a poem?

I reach for my lucky Mongolian fishing knife and sit in a chair on the other side of the room. The knife, my chair and the distance between myself and the screen tends to help. Or I get on my mountain bike and go for a short ride into the bush because turning my brain off to the poem usually brings a solution.

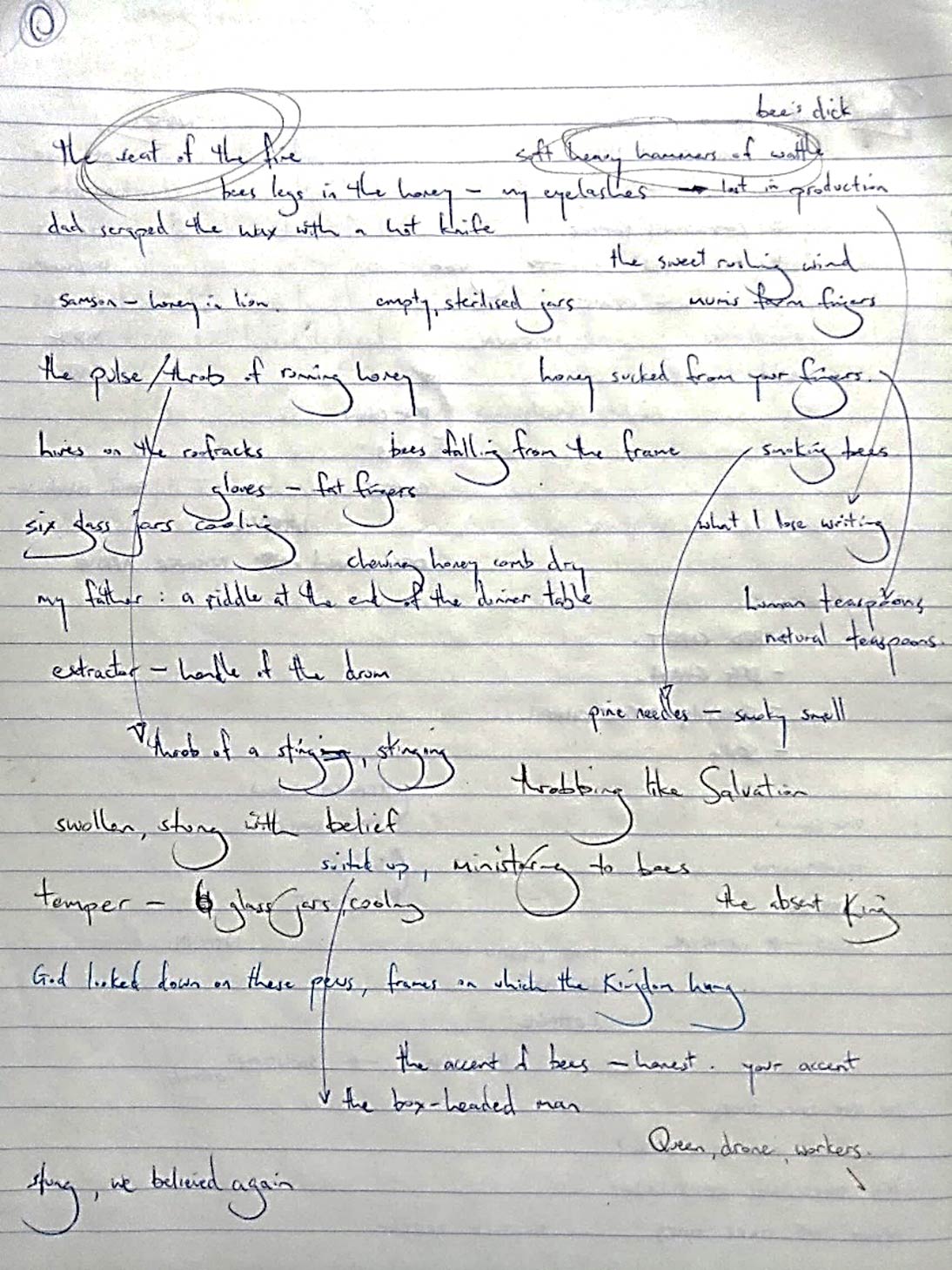

Take a photograph of a page from your notebook or a screenshot of an electronic file of a poem you have been recently writing or revising.

On Poetry:

Is there something you once believed about poetry that you no longer hold true? What changed?

I used to think inspiration was overrated. Now while it’s not always essential, I think our best poems generally come from answering some deep need or experience within us. The do-or-die poems that have to be written usually speak with a reason and energy above those that come as good passengers along the way.

Emerging writers often hear about the importance of routine and not just waiting around for inspiration. There’s good reason for that. But once you’re established I think you realise how valuable inspiration is. Some poets will disagree, and that’s okay, I get nervous if we agree too much.

What can/does poetry change?

Well, it changed me. It changes people, and people can change the world. Poetry is created and in turn, creates.

Everything that comes from the source of imagination and potential has the power to revolutionise.

Is there something you now think you know about poetry that you wish you’d known a decade ago?

That the more you release it of your expectations—i.e. what you can get from it, where it will take you—the more it will enrich your life.

Ten years ago, heady with drive and determination, I lacked patience and humility. To speak bravely and honestly you have to let poetry demoralise you.

It’s a lifetime process, and like life, you never really master it.

On Influence & Inspiration:

What books are on your night stand, the back of the toilet, your desk?

Lorrie Moore’s How to Become a Writer

Ted Hughes’ Crow

Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry

Kevin Brophy’s In This Part of the World

Which writer/s do you (re)read the most? What does the writing do for you upon return?

I keep returning to the Australian writers, Kevin Brophy and Cate Kennedy. Then there’s Sharon Olds, W. S. Merwin, and Pablo Neruda. A touch of Charles Bukowski from time to time. They each remind me of why I began writing and inspire me to find my own way.

Among the poets you most admire, who has influenced you the least? Why have you not been influenced by his/her work?

Wendell Berry. He’s a superb poet, but I just can’t dig the whole “simple-life goodness” of it all. He’s not wrong, he has an important message, but there’s too much prayer and praising in it for my liking.

Describe a moment from your life when you've been overcome by how beautiful something is.

I was out riding my bike recently and met a male kangaroo grazing at the edge of the bush. It was twilight and he rose up high, over six foot tall, just staring straight at me. He was a dignified chief without fear and we stayed in each other’s presence for the longest time until he smoothly, silently hopped away. It was like a dream, as if that moment had been sent to me.

On Teaching:

How would you describe poetry to a four-year-old? To the non-literary family ancestor you imagine as a great source of who you are?

Well, I can’t go past that third grader who said “poetry is an egg with a horse inside,” or else it’s an echidna trying to put on underpants. To the non-literary family ancestor I’d say, poetry is what I left at your grave that time. I’m not surprised you didn’t get it.

What characteristics does your ideal poem possess?

Ideas and images, focus and fault lines, rhythm and silence, feeling and intellect, humour and sincerity, the control and explosion of language, the wonderfully hopeless fullness of living. That’s a big ask.

More simply, poet Michael Bazzett says, “frame the room for the dream,” and I think that’s what an ideal poem does.

Do you teach poetry? If so, what are you trying to teach through poetry? What has poetry taught you?

I taught at university for a little while, but not anymore. These days I prefer to teach one-on-one and as informally as possible.

I find it hard to articulate the instincts I’ve developed, all the tiny decisions I make when crafting a poem. I guess I try to convey the vast range of what it can be; the inherent and addictive contradictions of the form; the infuriating joy of it and the sense that if you work hard you’ll improve.

The trouble is poetry constantly teaches me how little I know about it.

On Publishing & Themes Present/Future:

How has publishing your poems changed your writing practice, process, and product?

Publishing has provided perspective. I’ve had ample opportunity to look back and be reminded by my past work. Sometimes that’s not a pleasant experience. So it means I work harder to try and mitigate those moments down the line.

Is there a poem you've always wanted to write but haven’t? If so, why are you waiting?

Not particularly, but I’m planning to write a suite about Judas Iscariot and the varying accounts of how he died. I’m waiting because waiting is a part of it all, and right now the whole thing seems colossal.

What subjects, themes, forms, aesthetics, etc. do/will you explore in your work?

I’ll keep working in free verse and will probably give an entire collection to Judas at some point. I’d like to unhang him for a while.

Other than that, my usual themes will probably keep cropping up, e.g. faith, duty, family, love, and grief in the day-to-day.

On Oranges:

Oranges or apples? Why?

Yes. Because they’re fruit.

About the Poet

Nathan Curnow is an Australian poet and past editor of Going Down Swinging, one of Australia’s longest-running and most respected literary journals. His books include The Apocalypse Awards (Arcadia, 2016), The Ghost Poetry Project (Puncher & Wattman, 2015), and RADAR (Walleah Press, 2012). In 2018, Nathan toured Europe with loop artist, Geoffrey Williams, performing in Poland and opening the Literary Days Festival in Heidelberg, Germany.