Inter-

Conyer Clayton

On Practice:

Do you write at the same time every day, in the same place? How would you describe your writing practice/s?

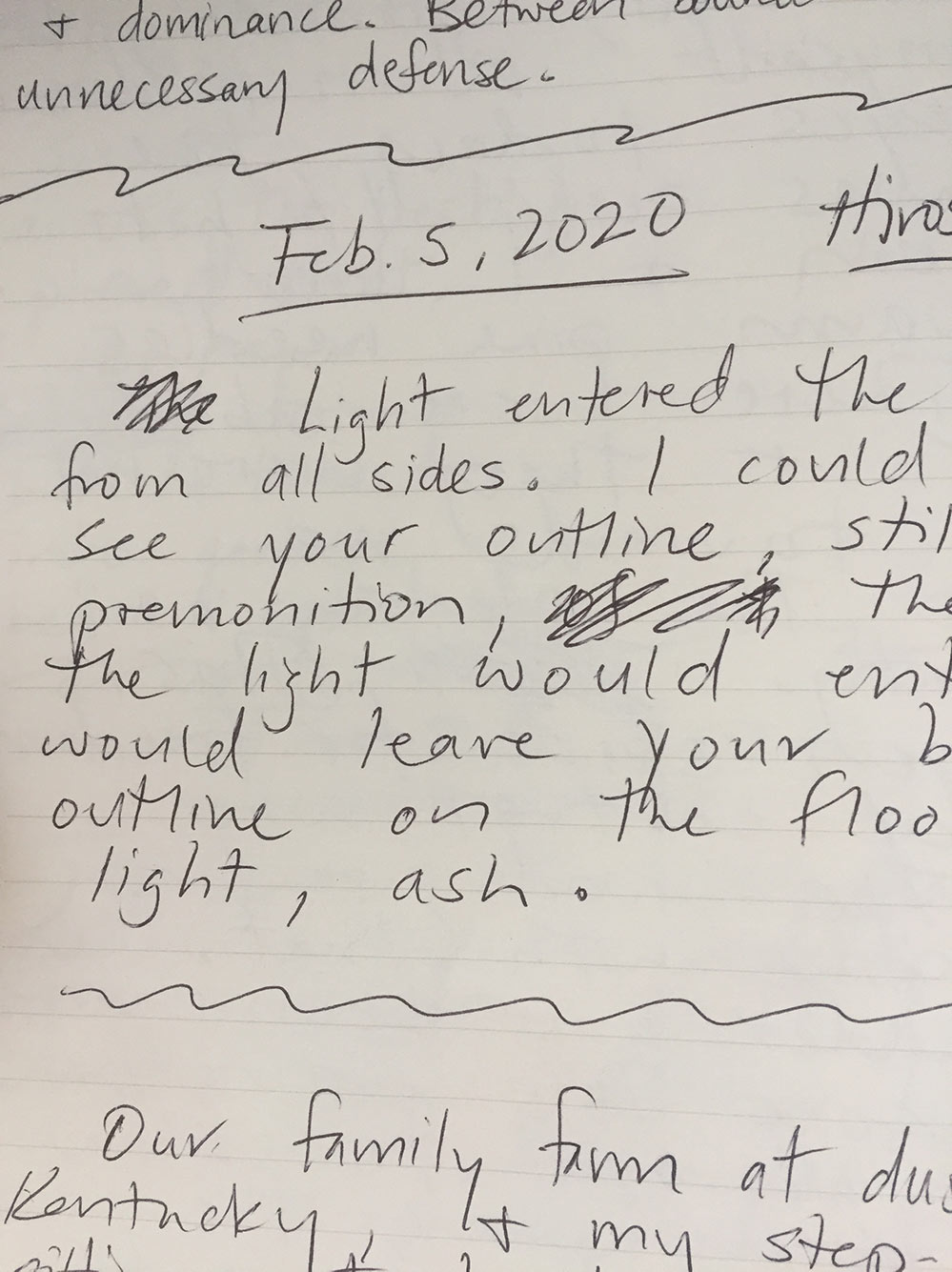

I usually write in the morning, but not always. Usually at my desk in the living room, but not always. I don’t force a specific practice on myself. Rather, I just wait for ideas and the need to write to come. Luckily, that need comes often. I like to keep the tap flowing. I always write by hand in my notebook first. It is the only way I can write without self-editing. Editing comes once a screen gets involved.

What do you do if you get stuck while writing a poem?

I just leave the poem alone—sometimes for years—until I feel a pull back to that piece. Or, I workshop it with one of my many brilliant writer friends here in Ottawa.

Take a photograph of a page from your notebook or a screenshot of an electronic file of a poem you have been recently writing or revising.

On Poetry:

Is there something you once believed about poetry that you no longer hold true? What changed?

Once I believed good contemporary poetry could not rhyme. I don’t believe that anymore. While rhyming is not my personal mode, being exposed to some incredible spoken word artists and rappers over the past few years, my partner, Nathanael Larochette included, has really shown me that contemporary poetry can rhyme and also be extremely good.

What can/does poetry change?

Poetry can shift the space inside of you, and from there, many things are possible—healing, acceptance, empathy, fortitude, and determination to change that which needs changing in the world, often starting with what needs changing in yourself.

Is there something you now think you know about poetry that you wish you’d known a decade ago?

To be honest, I think 10-years-ago-me could actually give present-me some pointers! She’d remind me to write for the sake of writing, without care at all for what is trendy. I really try to stay rooted in that, but geez, Twitter makes things hard sometimes! I look to early 2010’s Connie for inspiration on just putting pen to paper without concern for publication.

On Influence & Inspiration:

What books are on your night stand, the back of the toilet, your desk?

Night stand: Against Death: 35 Essays on Living (Anvil Press, 2019), Edited by Elee Kralji Gardiner

Stacked on my desk: Collected Poems of H.D. (New Directions, 1983), Everything is Awful and You’re a Terrible Person (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2017) by Daniel Zomperelli, Beasts of the Sea (knife fork book, 2018) by Kate Sutherland, The Lake Contains an Emergency Room by Lillian Nećakov (Apt. 9 Press, 2015).

I am not a toilet reader, lol.

Which writer/s do you (re)read the most? What does the writing do for you upon return?

Honestly, everyone probably wants me to shut up about Kaveh Akbar, but Calling a Wolf a Wolf (Alice James Books, 2017) is the book I revisit most often, and I will say it into eternity.

I also often reread random selections from Italo Calvino’s The Complete Cosmicomics (Mariner Books, 2002).

Coming back to a work feels homey, comfortable, even when what is being expressed is anything but. It helps me to be able to sit with those uncomfortable emotions or histories in my own story that I see reflected back.

Among the poets you most admire, who has influenced you the least? Why have you not been influenced by his/her work?

It is hard for me to quantify precise influence, or lack thereof, so I struggle to answer this question. I don’t think I could make the claim that something I’ve read and admired has not influenced me in some way.

Describe a moment from your life when you've been overcome by how beautiful something is.

Basically every time I’ve ever been in a forest. I am definitely a forest gal.

Also both times I’ve seen Richard Reed Parry’s Quiet River of Dust played live. I wept multiple times— for joy, for sadness, for grief and renewal and the intermingling of it all.

On Teaching:

How would you describe poetry to a four-year-old? To the non-literary family ancestor you imagine as a great source of who you are?

Poetry is music is poetry is music. It does not have to be “about” something for it to “mean” something. Stop looking for the “about” and just listen/read. What is the result? That is what it is “about.”

What characteristics does your ideal poem possess?

Wonder, or the total lack of it. Precision, or wildness. I think I like extremes. But all of my favorites have a tinge of surrealism, magic, a hint towards transcendence.

Do you teach poetry? If so, what are you trying to teach through poetry? What has poetry taught you?

I do not teach poetry, but poetry tries to teach me patience. I am working on it.

On Publishing & Themes Present/Future:

How has publishing your poems changed your writing practice, process, and product?

Publishing hasn’t changed my drafting process, but now that I have experience putting together chapbooks and a full-length collection, I begin intentional editing for some cohesion between poems, or towards a specific constraint, much earlier in my process.

Is there a poem you've always wanted to write but haven’t? If so, why are you waiting?

I’ve always really wanted to write an amazing sestina. I tried once, and failed so miserably that I haven’t tried again, and that was 10 years ago! Kiki Petrosino has an incredible sestina called “Political Poem” in her book, Witch Wife (Sarabande Books, 2017), that really informs me on what the form can do.

What subjects, themes, forms, aesthetics, etc. do/will you explore in your work?

My writing sets personal experience alongside the magical and surreal as a way of uncovering how the unconscious mind speaks to the conscious self. In my work, I try to validate the spaces between waking and dreaming, safe and unsafe, living and dead, remembered and not.

As a gymnast and dancer, my work is also deeply rooted in bodily experience; in how our mental state effects our physical state; in how trauma can manifest itself through our very skin.

I would like to explore my concrete experiences as a gymnast and gymnastics coach further in my work at some point, but it has not happened yet.

On Oranges:

Oranges or apples? Why?

This is the hardest question. Oranges taste better, but like... are annoying to eat. I am the awful person who sucks the juice from an orange slice and eats none of the flesh. I love apples too, though. Can I just say berries? Berries rule.

About the Poet

Conyer Clayton is an Ottawa-based writer with six chapbooks; most recently Trust Only the Beasts in the Water (above/ground press, 2019). Sprawl, written in collaboration with Manahil Bandukwala, is forthcoming October 2020 with Collusion Books. Her debut, full-length collection of poetry, We Shed Our Skin Like Dynamite, was released May 2020 from Guernica Editions. Conyer contributed “The Malice in My Footsteps,” to the Fall 2017 issue of The Maynard

Inter-

Jordan Abel

On Practice:

Do you write at the same time every day, in the same place? How would you describe your writing practice/s?

The more I talk to folks about writing, the more I think it’s important to be as transparent as possible when talking about my practice. I honestly mostly write when I am inspired to do so. Sometimes that means that I only write creatively for a few weeks every year. I know lots of writers who are really successful at sustaining daily practices, but I think there’s a certain kind of hidden privilege in being able to write at the same time in the same place every day for even an hour. The trick, for me, is trying to be okay with myself as a creative writer when I’m not actively writing. As I mentioned before, if I’m only writing a few weeks every year—and in those weeks it’s often quite intense, sustained writing—that means that for the majority of the year I’m not writing anything. It’s tough not to beat yourself up for not writing, not creating. But so far this is the practice that works the best for me.

What do you do if you get stuck while writing a poem?

I don’t often write poems anymore, but when I get stuck writing anything I often just have to walk away for a while. Sometimes a whole year!

Take a photograph of a page from your notebook or a screenshot of an electronic file of a poem you have been recently writing or revising.

On Poetry:

Is there something you once believed about poetry that you no longer hold true? What changed?

I used to think that in order to write something that would be later published as poetry that I had to try to write “poetry.” I gave that up a long time ago. Now I just write and whatever genre it happens to be, whatever the writing is, that’s what it is.

What can/does poetry change?

Sometimes I feel quite sad and think that poetry doesn’t do anything. But the more I think about it, writing does create community. Writing allows us to see each other. To understand difference. That, to me, is invaluable.

Is there something you now think you know about poetry that you wish you’d known a decade ago?

Early on folks made it pretty clear to me that you don’t write poetry to make money or to gain wide readerships. I think that knowledge sharing came from a mostly good place, but it was also discouraging. It’s not that I wanted those things necessarily. It’s that I had no choice but to write poetry because that’s the genre that fit my work the best at the time. I think better advice would have been to encourage writers to write the books they really want to write—regardless of genre—and sort the rest out later.

On Influence & Inspiration:

What books are on your night stand, the back of the toilet, your desk?

On my desk right now is A History of My Brief Body by Billy-Ray Belcourt (Hamish Hamilton, Aug 2020), Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019) by Reni Eddo-Lodge, and IRL (Birds Llc, 2016) by Tommy Pico.

Which writer/s do you (re)read the most? What does the writing do for you upon return?

Honestly? Bonita Lawrence. I keep re-reading certain sections of her book “Real” Indians and Others: Mixed-Blood Urban Native Peoples and Indigenous Nationhood (UBC Press, 2004). But I also have been rereading Tommy Pico’s Nature Poem (Tin House Books, 2017), as well as Citizen (Graywolf Press, 2014) by Claudia Rankine.

Among the poets you most admire, who has influenced you the least? Why have you not been influenced by his/her work?

HA! I absolutely love Eden Robinson’s work but could never write like her. Perhaps that is a genre thing, though! I don’t think a narrative prose work is in the cards for me any time soon. Especially not one that involves any characters or dialogue.

Describe a moment from your life when you've been overcome by how beautiful something is.

When I was teaching Indigenous Literatures last semester, I had so many Indigenous students come up to tell me that Tenille Campbell’s #IndianLovePoems (Signature Editions, 2017) was their new favorite book ever and a book that after years of reading for university classes finally felt like it actually spoke to them. I thought that was totally incredible.

On Teaching:

How would you describe poetry to a four-year-old? To the non-literary family ancestor you imagine as a great source of who you are?

It’s sometimes words but also sometimes not and sometimes it has line breaks but also sometimes not.

What characteristics does your ideal poem possess?

Something that feels honest and truthful in some meaningful capacity.

Do you teach poetry? If so, what are you trying to teach through poetry? What has poetry taught you?

I do teach poetry! I am constantly learning what does and what doesn’t work. But right now I’m very much focused on teaching students to write through form—since many of them don’t gravitate to form on their own—but also to read widely within poetry. My poetry class for the fall has an extensive list of poetry books for the course reading (as opposed to anthologies or single poems). The poetry book itself is such an important space for many poets.

On Publishing & Themes Present/Future:

How has publishing your poems changed your writing practice, process, and product?

Publishing poetry has really been such an incredible process for me. I didn’t realize that poetry publishing is such a labour of love in many cases. You really have to believe in that project and the publisher really should believe in it too. I feel so incredibly lucky to have worked with two publishers that really love and understand what it is that I’m trying to do. In this way, I’ve really come to think about writing and the publishing of that writing, to be very much based around a relationship of trust and understanding.

Is there a poem you've always wanted to write but haven’t? If so, why are you waiting? What subjects, themes, forms, aesthetics, etc. do/will you explore in your work?

My dream used to be to write a long poem—a book length poem—and I somehow managed to make that happen! My next dream is to write a novel-length work of prose without any characters or plot. Which is what I’m working on right now!

On Oranges:

Oranges or apples? Why?

Oranges! Because I think I’m mildly allergic to apples

About the Poet

Jordan Abel is a Nisga’a writer from Vancouver. He is the author of three books published by Talonbooks: Injun (2016), which won the Griffin Poetry Prize; Un/inhabited (2015), which includes writing by curator Kathleen Ritter, and The Place of Scraps (2013), which won the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. NISHGA is forthcoming from McClelland & Stewart in 2020. Currently, Abel is an Assistant Professor at the University of Alberta. Jordan contributed “Indian (4) “ and “Blood Quantum (8 – 9) “ to the Fall 2016 issue of The Maynard.