Inter-

Eleanor Kedney

On Practice:

Do you write at the same time every day, in the same place? How would you describe your writing practice/s?

I write in the morning when waking consciousness is closer to the dream state. At this time of day there is a greater possibility that a deeper truth will surface from my subconscious. Writing is less structured for me than in the past. I don’t sit at a desk and wait to be inspired. When images or lines or titles come to me, I trust them, and jot them down. They percolate inside me, and I write. It’s an exploration.

What do you do if you get stuck while writing a poem?

If I am stuck while writing or completing a poem, I put it aside. When I return to it I add new images, or open up the images I’ve written, until I am able to take the poem in the direction it wants to go. Once, when taking a walk after it rained, I saw something that gave me the last line of a poem I was struggling to finish. To allow the poem to become what it wants to be often means letting go of lines I love that don’t work and being receptive to what is being excavated—the deeper layer of meaning or emotion. If my syntax becomes awkward, it’s a cue that I need to find a way, usually through craft, to connect to an uncomfortable emotion.

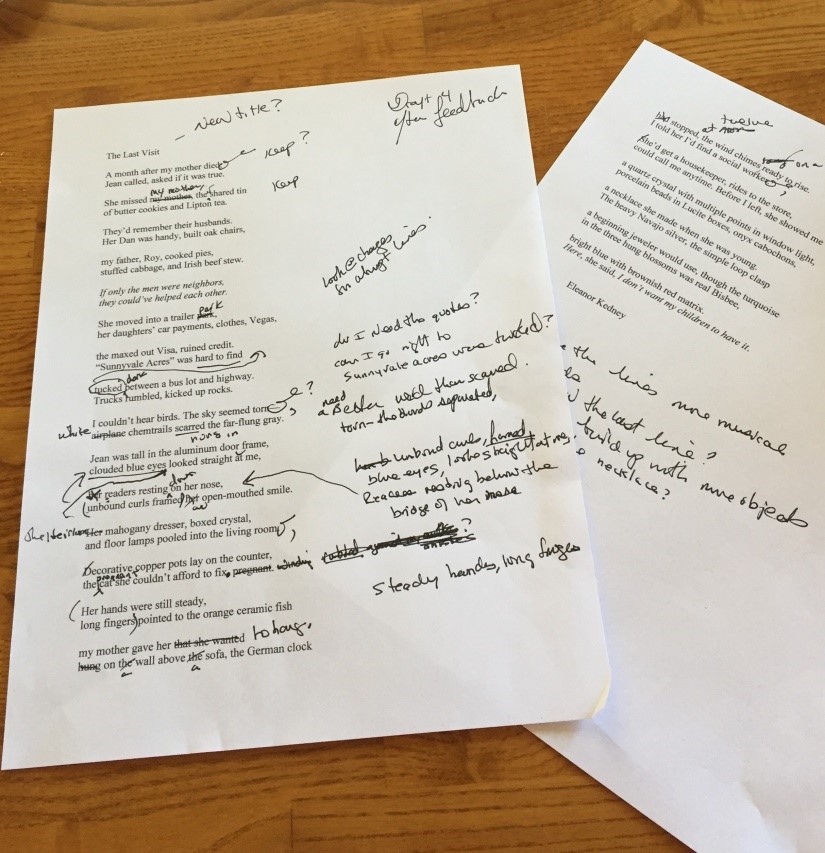

Take a photograph of a page from your notebook or a screenshot of an electronic file of a poem you have been recently writing or revising.

On Poetry:

Is there something you once believed about poetry that you no longer hold true? What changed?

My beliefs about poetry, my own poems, have evolved, but it doesn’t mean that things I believed in the past may not apply in specific instances. If I had to choose something, I’d say I no longer feel I have to know what a poem is about when I start writing.

What can/does poetry change?

Poetry can change the writer’s and reader’s perspective about things that have happened to them. It can validate feelings. A poem offers a take on a subject and allows the reader their emotional response. It gives us passage through grief and pain to greater understanding. A poem is like receiving a hug from a good friend or loved one.

Is there something you now think you know about poetry that you wish you’d known a decade ago?

Yes. I would have liked to know that if I create a strong mood with description, I don’t have to go directly at difficult emotions. Doing so enables me to deepen a poem by working with both the narrative and lyric. I have a strong connection to nature and animals, and when I turn to one or the other I find answers and meaning.

On Influence & Inspiration:

What books are on your night stand, the back of the toilet, your desk?

The book that sits on the corner of my coffee table depends upon what I am writing at the time. It could be a book by Jack Gilbert, Henri Cole, Grace Shulman, Ross Gay, Alicia Ostriker, Meghan O’Rourke, or Margaret Gibson. I’ve studied with Philip Schultz and Juliet Patterson and learn from their poems. I read the work of friends, such as Robert Carr, Megan Freeman, and Jami Macarty.

Which writer/s do you (re)read the most? What does the writing do for you upon return?

I return to Jack Gilbert to study how he seamlessly moves from description to saying something directly to the reader that is universal, and then adds a turn in the poem to bring in the personal. In his poem “Measuring the Tyger” (The Great Fires poems 1982-1992, Knopf), he accomplishes all of this and skillfully manages two turns in the poem.

Among the poets you most admire, who has influenced you the least? Why have you not been influenced by his/her/their work?

Ted Kooser’s poems are rooted in a Midwestern setting, and he draws from common speech. The narrative voice is conversational. My poems tend to employ a celebratory tone in contrast to a dark mood. And although I often write poems that draw upon a locale, such as the desert, my poems don’t address the concerns of my everyday life in Tucson.

Describe a moment from your life when you’ve been overcome by how beautiful something is.

Lying on the floor looking into the eyes of my dog Jackalyn the day she died. Our connection was so strong, so beautiful. I’ll never forget that moment.

On Teaching:

How would you describe poetry to a four-year-old? To the non-literary family ancestor you imagine as a great source of who you are?

Writing poetry is like celebrating Halloween (my birthday). You can choose a mask and a costume and become any character you want. The character is a narrator who can say all the things you want to say. You are free to move your body in new and playful ways, too. Poetry celebrates voice, breath, one’s imagination, and emotions.

What characteristics does your ideal poem possess?

Lately, poems both impress and disappoint me. It may have something to do with my age, and the urgency I feel to both write and read poetry that makes a positive contribution to the world. An ideal poem has striking images that are fresh and unfamiliar, and at least one line that feels true. The poet has dug deep and struck oil. I can’t dismiss the line; I carry it around all day. Usually, I wish I had written such a line. I want to be both deeply moved and challenged to write better poems.

Do you teach poetry? If so, what are you trying to teach through poetry? What has poetry taught you?

I am retired from teaching poetry and fiction for The Writers Studio. I believed in my students when other teacher’s didn’t, and for one very special writer, it changed his life. Teaching craft elements gives writers the tools to fully express themselves. It is often said that we teach what we need to learn, and in teaching craft, I learned ways to access my emotions. Poetry has taught me that what is true in one moment may not be true in another, and that each poem I write is both an exploration and discovery. It makes living exciting.

On Publishing & Themes Present/Future:

How has publishing your poems changed your writing practice, process, and product?

When I first started to publish, it gave me confidence. Acceptances are thrilling to receive and they offset the disappointment I feel from rejections. Acceptances and rejections have taught me to be more true to what I want to say and trust myself. One editor may feel a poem is not yet fully realized, while another may think it’s the best thing they read all day. So, I don’t write to publish; I write to become a better writer and a better person.

Is there a poem you’ve always wanted to write but haven’t? If so, why are you waiting? What subjects, themes, forms, aesthetics, etc. do/will you explore in your work?

I want to write a poem that is widely read and remembered. One example of such a poem is Robert Pinsky’s “Shirt” (The Want Bone, HarperCollins). A famous poem gives the poet name recognition; however, more importantly, it means the poet has written something that has touched a great many people and is deeply connected to our humanity. To write that kind of poem would mean that I not only understand something about writing poetry, but that I care deeply about how poetry can help us understand each other and our own lives. I’m currently exploring the theme of choice, and how we are affected when a choice is taken from us.

On Oranges:

Oranges or apples? Why?

Apples. There is a poem in my book Between the Earth and Sky titled “Apple Pie.” My father made the best apple pie. The poem expresses the love and delight he put into making the pie, and the special early morning moments watching him rolling dough and fluting the crust. The last line of the poem reveals the loss the narrator feels after the father dies and there is one piece left. I’ll leave it at that, so people who read the poem can experience the ending for themselves.

About the Poet

Eleanor Kedney is the author of the full-length collection Between the Earth and Sky (C&R Press, March 2020) and the chapbook The Offering (Liquid Light Press, 2016). Her poem “Bubbles Blown through a Wand” won the 2019 riverSedge Poetry Prize (University of Texas Rio Grande Valley). Kedney is the founder of the Tucson branch of the New York-based Writers Studio, and served as the director for ten years. Visit: https://www.eleanorkedney.com/.

Inter-

gary lundy

On Practice:

Do you write at the same time every day, in the same place? How would you describe your writing practice/s?

I tend to write in coffee shops. Have for years. And not the fancy new ones, but the ones with character. Since arriving in Missoula I hang out at Butterfly Herbs. It’s a nice environment to get work done. I will read and write in the morning for a couple hours, and then after I do something else like visit with a friend, write again in the afternoon for another couple hours. Although, honestly, the writing comes when it’s ready, even in the middle of the night.

What do you do if you get stuck while writing a poem?

I stop writing. I’m not particularly interested in “intentional” writing. The kind of writing that sets out to accomplish some prescribed narrative. Rather, I sit and a fragment of a phrase or a few words catch my ear and I jot them down. Then I listen to see where they lead. It’s always a delightful adventure, and one that teaches me so much about myself and this world I happily inhabit.

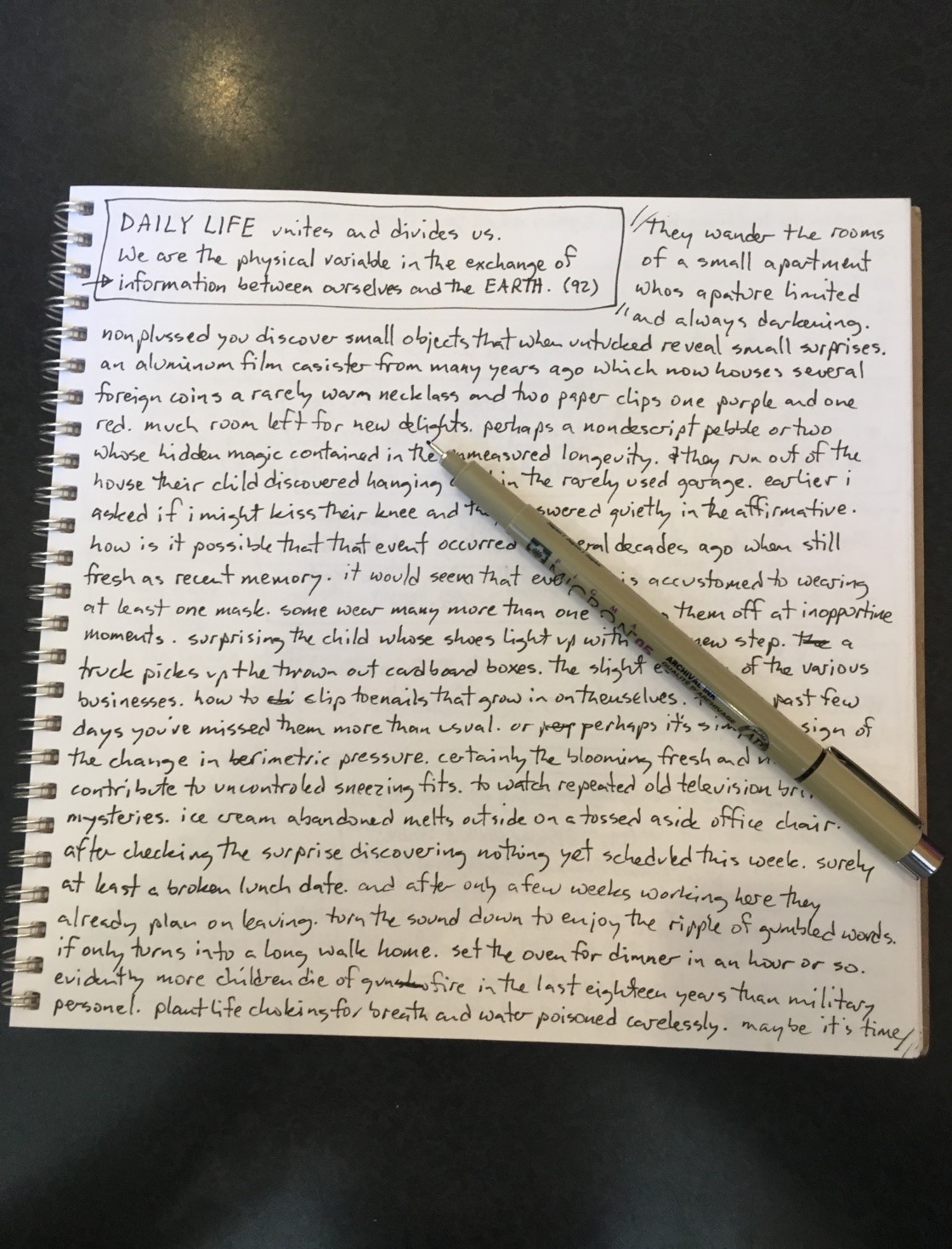

Take a photograph of a page from your notebook or a screenshot of an electronic file of a poem you have been recently writing or revising.

(The blocked off text is from Personal Volcano, by Laura Moriarty.)

On Poetry:

Is there something you once believed about poetry that you no longer hold true? What changed?

For many years I believed poetry had to be rooted in the personal, and in the real—or what we perceive to be real. While the melody of language was important, it was the “message” that mattered most. That and what I refer to as the “aha” moment. Poetry had to be lyric and certainly wedded to personal experience. It needed to be easily understood.

This all changed when I discovered Nicole Brossard’s Lovhers (Guernica Editions, 1986). I had the pleasure of meeting Brossard on a campus where I then taught. I was so impressed with her talks, her readings. After she left I couldn’t wait to read her new book. It took me upwards of six months to be able to read it though. Her poems introduced a form of writing I was completely unprepared for. Had I not been so impressed with her I probably would have given up. Thankfully I didn’t. Once I let go of the prescribed rules I’d been taught were essential to poetry I found a writing that introduced new rhythmic dynamics as well as a beautiful, even if unfamiliar form. I was hooked. The idea of fragments grew as the sense of continuity decreased.

What can/does poetry change?

I would hope that poetry reintroduces us, the readers, to the joy and open-endedness of language, the play of language, if you will. It also reintroduces us to the playful contained within language, and the variety of music and rhythm. I would similarly hope that poetry introduces us to the breadth of language, to it’s nuances and accidents. Finally, I hope that poetry invites us to call into question our comfortable sense of familiarity with language—that words speak more and less than intended.

Is there something you now think you know about poetry that you wish you’d known a decade ago?

Everything in the last three paragraphs! Although this would have to be two decades honestly. Seriously, I wish I’d have trusted what I was given to write rather than puzzling over how to fit this into the model I’d been taught was essential to successful poetry. To perhaps repeat myself: that poetry included far more than lyric privilege and narrative structure.

On Influence & Inspiration:

What books are on your night stand, the back of the toilet, your desk?

Two right now that I’m excited to get to— Rosmarie and Keith Waldrop, Keeping / the window open: Interviews, statements, alarms, excursions, Edited by Ben Lerner; and, Troubling the Line: Trans Poetry and Poetics, Edited by TC Tolbert and Trace Peterson.

Which writer/s do you (re)read the most? What does the writing do for you upon return?

There are a number of writers I return to. Nicole Brossard, of course, Rosmarie Waldrop, Lisa Robertson, Laura Moriarty, Erin Mouré, Leslie Scalapino are a few. I tend toward writing by women. I think that’s because it invites me to examine my sense of privilege and what I accept as normal, or real. Also, it seems to me there is an act of redefining a/the sense of identity which rarely comes up with especially straight male writers. Perhaps because I have for years identified as queer, and because for a good part of my life I had no place within which to feel comfortable and alright with my sense of hidden self, I gravitated to women writers and their work to broaden the field of identity and self.

Among the poets you most admire, who has influenced you the least? Why have you not been influenced by his/her work?

Honestly I don’t know if there is a writer I admire whose writing doesn’t or hasn’t influenced me. I tend to gravitate to those writers whose work compels.

Describe a moment from your life when you've been overcome by how beautiful something is.

Recently I met friends’ newborn baby, and had to sit down. Such magical beauty.

On Teaching:

How would you describe poetry to a four-year-old? To the non-literary family ancestor you imagine as a great source of who you are?

I’d not describe poetry to a four-year-old, especially. Rather, I’d talk with them about their sense of language, words, etc. And I’d listen carefully. I suspect that young children have a great deal to teach us about poetry. The four-year-olds I’ve met seem to have a sense of language that delights in sound, in the comic aspect of language, in particularities. They haven’t yet learned to measure everything from a distance.

Were I speaking to a family ancestor, I suppose I’d encourage them to take a break from what they think language is and does, and to listen for the unexplained and unexpected connections between words, fragments, and lines.

What characteristics does your ideal poem possess?

I suppose my ideal poem would not abide by over-rehearsed writing and structure. It would surprise even as it inevitably confused. It would require careful consideration at the same time as it demanded playfulness. It would hopefully offer unexpected viewpoints. Finally, such a poem would be strange and situate language outside those convenient boundaries of the easily ascertained and/or dismissed.

Do you teach poetry? If so, what are you trying to teach through poetry? What has poetry taught you?

I taught poetry for many years. In both my poetry workshops and literature classes focused on poetry I hoped to reacquaint my students with the pleasure of a language free from the educated measure of language as simple tool. Perhaps along the way they might begin to consider words as not only a tool but also as a guide into what isn’t known but is. This is certainly what I continue to learn from reading and writing a kind of poetry.

On Publishing & Themes Present/Future:

How has publishing your poems changed your writing practice, process, and product?

Early in my writing practice when a poem was published I gathered a great deal of affirmation, and, perhaps, too, a kind of permission to continue writing. At this point in my life when a poem is published I see it more like finding a home for the poem. It still feels wonderful, of course, but I have less of a need for the affirmation of/toward writing practice, if you will.

Is there a poem you've always wanted to write but haven’t? If so, why are you waiting? What subjects, themes, forms, aesthetics, etc. do/will you explore in your work?

Not for a long time, if ever. I write what I’m given to write and enjoy that activity. In that way I am forever surprised.

On Oranges:

Oranges or apples? Why?

Oranges! They are so juicy, and get all over hands and face, lips and fingers!

About the Poet

gary lundy is the author of five chapbooks, including when words detach themselves (is a rose press, 2013), and at | with (Locofo Chaps, 2017), and two full-length collections: heartbreak elopes into a kind of forgiving (is a rose press, 2016), and each room echoes absence, (FootHills Publishing, 2018). Contributor to Fence, filling Station, and The Maynard (Fall 2015), gary is a retired English professor and queer living in Missoula, Montana.