Inter-

Elana Wolff

On Practice:

Do you write at the same time every day, in the same place? How would you describe your writing practice/s?

My writing practice is disciplined but eclectic, if that makes sense. I write daily, often at night—by turns creating, revising, tweaking, and reading. For me, reading is part of writing and sometimes ‘counts’ for writing, when the writing is stuck. If I’m at the ‘grazing stage’ of making a poem—penciling words, images, phrases or lines—I like to lie on the sofa with my head and feet propped up and a pad in my lap. Lying supine puts me into the liminal space of mind that nurtures poems. I still prefer pencil or pen and paper to screens for the initial stage of creating. When I get to the shaping stage, I sit—increasingly at the computer, to avoid crossing out and wasting paper. I always sit if I’m writing prose, most often at my desk or the kitchen counter. Prose comes from a different place than poetry and I’m not drawn to writing it lying down, though that’s the way Proust wrote his. Often I jot notes in the car, too, though not while driving.

What do you do if you get stuck while writing a poem?

Set it aside, go for a walk, read (as mentioned), paint, clean, cook, and sleep. Sleep is a great unfolder. I can take a poetry question into sleep and the next day an image or idea will suggest itself. Not always but often enough. This works with questions unrelated to poetry as well.

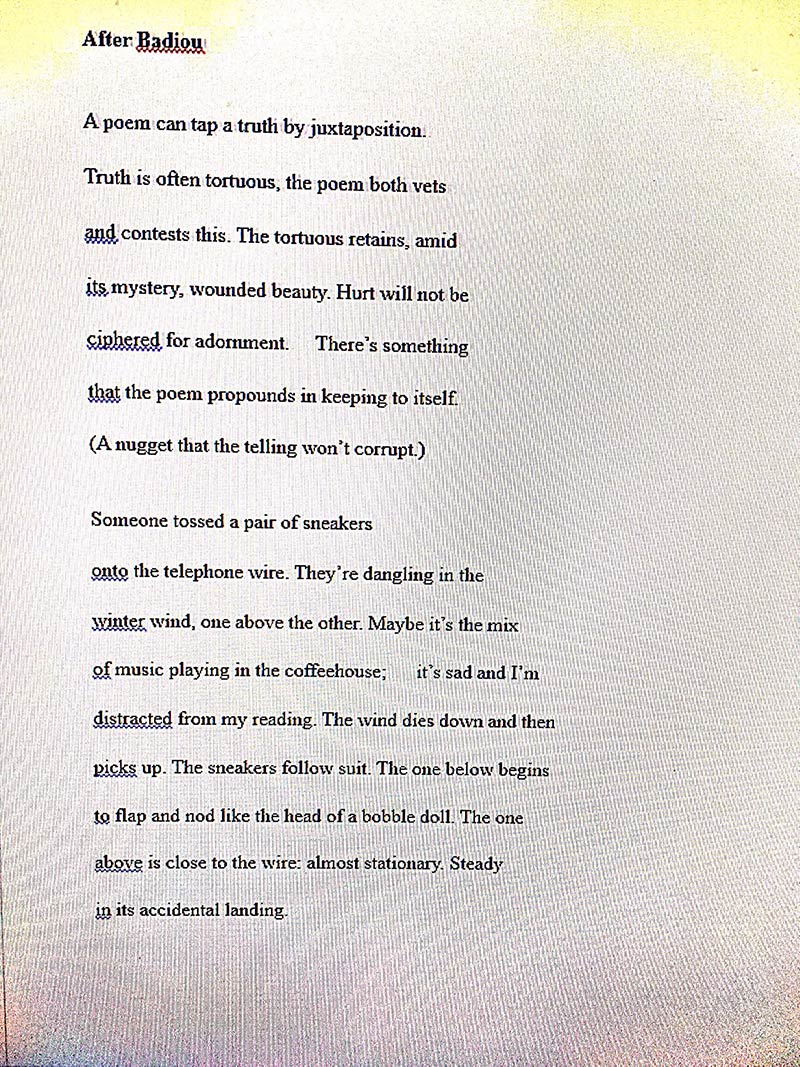

Take a photograph of a page from your notebook or a screenshot of an electronic file of a poem you have been recently writing or revising.

“After Badiou” is a poem I’ve revised countless times (and I could still tinker with it). It started with a reading of Alain Badiou’s, The Age of the Poets. I was wrangling with Badiou’s theory that truth is both eternal and unchanging (Platonic) and also constructed through processes (postmodernist). I attempted to work this mix into the poem through image and anecdote and have probably failed miserably at Badiou. But maybe the piece works on the level of rhythm and tension.

On Poetry:

Is there something you once believed about poetry that you no longer hold true? What changed?

I used to think that poetry doesn’t make much of a difference, despite my love of it. Maybe this thinking came from the general stance that poetry is a ‘small form’, that poetry books are typically not bestsellers, and that poetry has been considered by many to be a stepping-stone to writing prose fiction. As if poetry is somehow lesser or preliminary—the literary equivalent of crawling, and novel-writing to walking upright. There are many fine writers who wrote poetry first, then shifted focus to writing novels: Michael Ondaatje, Michael Redhill, Anne Michaels, and Margaret Atwood to name a few. Just as there are fine writers who started with poetry and stayed close to it—like Emily Dickinson, Elizabeth Bishop, Seamus Heaney, and Philip Larkin to name another few. It’s not a matter of rank. One writes what one is drawn to writing and in the form that best enables what one needs to express. I gradually discarded my earlier thinking through experiencing over time the difference poetry made in my life, also through learning of the difference poetry has made in the lives of others. I’m comfortable with the ‘small form’ and ‘minority’ status. I like compactness, also the minor key.

What can/does poetry change?

Poetry, in my experience, is restorative. More than making music, painting and drawing—other forms of creativity I engage in—writing (and reading) poetry has lifted me up when I’ve been at the end of my strength. It’s provided a way of channeling chaotic emotional and cerebral energy. Poetry can change the brain: This is what I’ve come to think. One only has to work hard at it.

Is there something you now think you know about poetry that you wish you’d known a decade ago?

Not long ago I read a piece by the Chilean/Mexican/Spanish writer Roberto Bolaño in the posthumous collection Between Parentheses in which he argues that “the immigrant, the nomad, the traveler, and the sleepwalker all exist, but not the exile, since every writer becomes an exile simply by venturing into literature, and every reader becomes an exile simply by opening a book.” This spacious take on exile was freeing and affirming for me, and it struck a poetry chord. Bolaño, whose phenomenal novels The Savage Detectives (English translation 2007) and 2666 (2004; English translation 2008) blew me away with their elegance and violence, was a poet first. He published five collections of poems and though he joked that “almost no one has read my poems, which is probably a good thing,” poetry always remained a focus in his prose fiction too. Bolaño lived his shortened life—he died at 50 in 2003—loving poetry in a badly fallen world, and he never considered that a bad joke. It might have been nice for me to have had Bolaño’s kind of faith in poetry a decade or more ago, but I had to come to it slowly, through experience, in my own time. There’s no fallback to wishing.

On Influence & Inspiration:

What books are on your night stand, the back of the toilet, your desk?

I have stacks of books on my desk, my night table, the kitchen table, and on the floor of my study. None on the back of the toilet! And no room on the shelves. Kafka’s books and books relating to Kafka have a place in all the stacks, as I’m working on a large Kafka project and he occupies much of my landscape. I recently read Michael Ondaatje’s new novel, War Light, and David Grossman’s A Horse Walks into a Bar, and I’m currently reading Rachel Cusk’s Kudos, so these are at the top of the bedroom stack. Home and Away: Writing the Beautiful Game by Karl Ove Knausgaard and Fredrik Ekelund is on the kitchen stack as I’ve been following the World Cup. Alice Oswald’s poetry collection Falling Awake has lately claimed a top spot on my desk along with Granted by Mary Szybist and Shallcross by C. D. Wright.

Which writer/s do you (re)read the most? What does the writing do for you upon return?

Nowadays I read and reread Kafka the most. Kafka is a preoccupation. It’s not only the writing that I return to but the life. I’m immersed in it. W. G. Sebald’s work is also inexhaustible and I regularly reread Vertigo, The Rings of Saturn, The Emigrants, and Austerlitz. Both Kafka and Sebald take me into worlds and literary spaces that in some ways feel more akin to me than the living ones. I’ve had my Hermann Hesse period, my Simone Weil period. I also return to the works of Turkish author Orhan Pamuk, Icelandic author Halldór Laxness, and Haruki Murakami, and I like to read the stories of Hebrew writer Shmuel Yosef Agnon aloud. Agnon’s world is so viscerally different from this one. In poetry I go to Louise Glück, Lucie Brock-Broido, Mary Szybist, and C. D. Wright. Also Mark Strand, Jack Gilbert, and Charles Simic. Returning to work is necessary to deep appreciation, in the way that revising is necessary to writing.

Among the poets you most admire, who has influenced you the least? Why have you not been influenced by his/her/their work?

I admire Anne Carson very much: Short Talks, Eros the Bittersweet, Glass, Irony and God, The Beauty of the Husband and Men in the Off-Hours are favourites. A few years ago I wrote a long response to pieces in Short Talks for Brick Books 40th Anniversary Celebration of Canadian Poetry. One can admire and appreciate without wanting to emulate.

Describe a moment from your life when you’ve been overcome by how beautiful something is.

I am often struck by the beauty of synchronicity—when something unlikely or unexpected happens to evince indubitable connective significance. In synchronicity, faith, knowing and amazement converge. It is the beauty of timing, which is so mystical.

On Teaching:

How would you describe poetry to a four-year-old? To the non-literary family ancestor you imagine as a great source of who you are?

The best way to “describe poetry” to a four-year-old is to say it and sing it. Even tiny babies respond to rhythm, rhyme, and melody. Poetic ‘devices’ are readily grasped and imitated by the young and very young without any explanation. Description is a distancing. This applies to the non-literary family ancestor as well. Read or recite to the ancestor an accessible ‘source piece’—one that has the “right words in the right order,” to paraphrase Coleridge, and the piece will speak for itself.

What characteristics does your ideal poem possess?

It has to work on my heart and head. It best be plangent, and magical. It should grip, lift, and take me in. Not let me down. It makes me want to write in ways that make my poem a better piece.

Do you teach poetry? If so, what are you trying to teach through poetry? What has poetry taught you?

I don’t teach poetry. But I do design and facilitate social art courses. I work with older adults in a multi-ethnic community setting and I introduce sessions with short quotes that pertain to the art processes. Sometimes I bring poems, or parts of poems. I have one of the students read the quote aloud, then I reread it and indicate connections. My aim is not only to involve the students and introduce the art processes by way of complementary text. I also want the group to hear how the lines of a poem come through the body, and resonate. How appeal and meaning are carried in cadence. How meaning can be plucked from an image or phrase, instinctively, whether or not one ‘understands’ the whole of a quote. How a quote from a poem can be a window, an impulse, an imagining. This is some of what poetry has taught me and what I aim to ‘pay forward’.

On Publishing & Themes Present/Future:

How has publishing your poems changed your writing practice, process, and product?

Practice and process are private and personal, and to a great extent independent of publishing. I write what I write and have to trust that my work will find its rightful place and reader. Once a piece is written and I consider it fit to submit, I look into journal calls, themes, and guidelines. I may or may not already have a journal or issue in mind. If a journal has published my work before, it might do so again. So there’s the tendency to pursue the route where one has had success. But there are no guarantees and expectations have to be kept in check. This applies not only to poetry and publishing. One has to develop resilience, be gracious, reach out for new opportunities, and resist resting on laurels. I have learned to look at work that’s been returned with a freshly objective lens. And more than once I’ve been relieved to have had the opportunity to rewrite. Thankful that a piece was not published in an earlier version. Happy to resubmit.

Is there a poem you’ve always wanted to write but haven’t? If so, why are you waiting? What subjects, themes, forms, aesthetics, etc. do/will you explore in your work?

There’s always the next poem, the poem not yet written, the blank page, the gap. The writer is a writer, as Kafka says, even when s/he’s not writing. Right now I’m straddling poetry and creative nonfiction. Honing poems for a sixth collection and working on a Kafka-quest project that involves travel, deep reading, strong mental and emotional commitment, and waiting. Waiting is a big part of the process.

On Oranges:

Oranges or apples? Why?

Oranges for their colour and apples for their tang: Pink Ladies. I’ll take both, please.

About the Poet

Elana Wolff is a Toronto-based writer, editor, and designer and facilitator of social art courses. Her poems and creative non-fiction pieces have appeared in Canadian and international publications and have garnered awards. Elana’s fifth collection of poems, Everything Reminds You of Something Else, was released with Guernica Editions in 2017.

Inter-

Ken Pobo

On Practice:

Do you write at the same time every day, in the same place? How would you describe your writing practice/s?

No, I don’t write at the same time each day, though mornings are generally better than evenings. My practice is to get my ass in the chair and do it. I don’t wait for inspiration. Ideas are busses and new ones come along pretty regularly.

What do you do if you get stuck while writing a poem?

That doesn’t happen much as my first draft comes out pretty fast. If I’m stuck, I go out to the garden, get myself away from drafting. Or I listen to music. Some drafts aren’t meant to go anywhere, but they may get me someplace better.

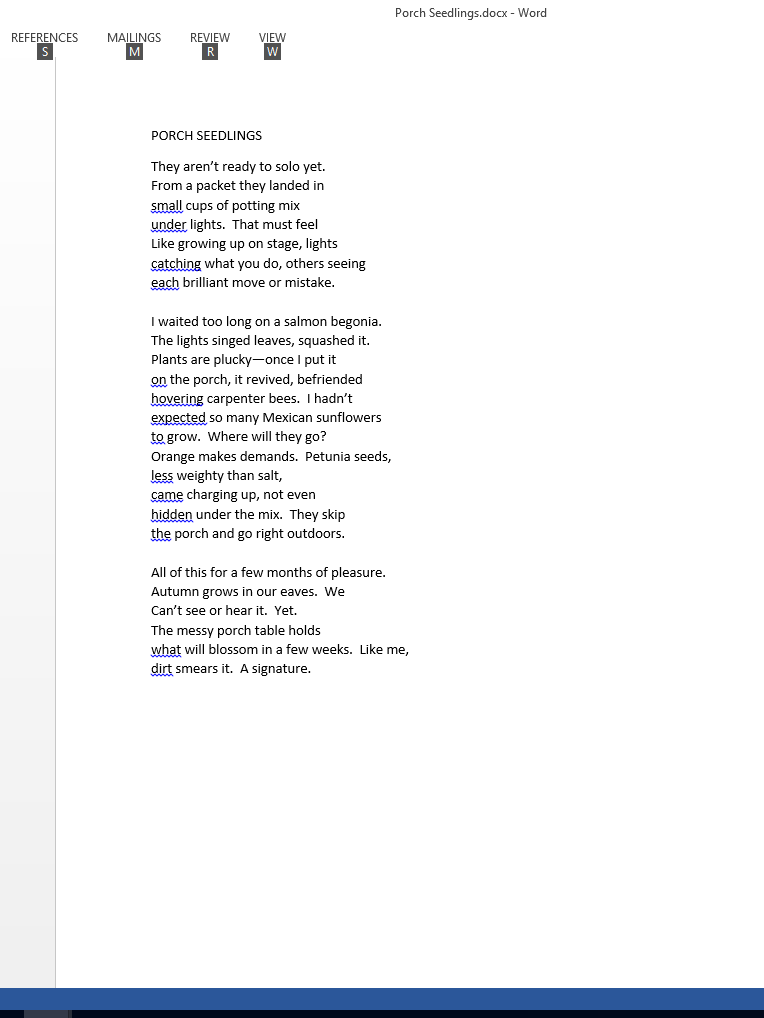

Take a photograph of a page from your notebook or a screenshot of an electronic file of a poem you have been recently writing or revising.

On Poetry:

Is there something you once believed about poetry that you no longer hold true? What changed?

When I started studying poetry, I was pretty much a modernist. But those poets rarely spoke to my issues as an LGBTQ+ person. I wanted to get more free of heterosexist paradigms. That’s a lifetime journey. Poetry is liquid. It may freeze over but spring comes too.

What can/does poetry change?

It changes me. I have to see differently, more clearly, more openly. In the long run, it may contribute to societal change, but right now it can do much for anyone with an open heart. Poetry makes looking out the window a pleasing requirement.

Is there something you now think you know about poetry that you wish you’d known a decade ago?

Not really. Roethke said, “I learn by going where I have to go.” I always wish I knew more, was more awake. But the journey continues and I change as I go.

On Influence & Inspiration:

What books are on your night stand, the back of the toilet, your desk?

No toilet books. My desk has loads of compact discs but no books. My night stand has a bio of Queen Victoria by Julia Baird, which I am enjoying. I’m a professor, so my school office is one big book clutter. Many of those books such as Buddenbrooks by Thomas Mann or The Collected Poems of Stevie Smith are never far away.

Which writer/s do you (re)read the most? What does the writing do for you upon return?

Thomas Hardy. I always go back to him. Anne Sexton’s Transformations. Lucille Clifton. Roethke. Transtromer. O’Hara. Just this year I rediscovered reading Gwendolyn Brooks. There are many. They help me. Even if they are gone, they are living. In me. And that gives me a runway to start writing.

Among the poets you most admire, who has influenced you the least? Why have you not been influenced by his/her work?

This one is hard as I think the poets we love all influence us in ways we may not see. Zbigniew Herbert is important to me, but he may not “influence” my writing except in that he created a character, Mr. Cogito, that impacted me. Truth is, if I love someone’s work, it’s there. How can it not be?

Describe a moment from your life when you've been overcome by how beautiful something is.

Every day in the garden I’m struck by wooooow moments. With poetry, I discovered Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem “Binsey Poplars” when I was in college—four decades ago. Its beauty and personal connections have only grown with time. And songs. I’m struck by the songs I adore like “12:30” by The Mamas and the Papas.

On Teaching:

How would you describe poetry to a four-year-old? To the non-literary family ancestor you imagine as a great source of who you are?

It wasn’t a four-year-old but I did talk to a group of third graders. How easily our talk of poetry went from poems into turtles. And they were excited to share what they knew about turtles. That’s poetry. In motion. In speech. For four year olds, I think I wouldn’t worry about definitions. I’d have fun and let the child say what he or she thinks about the world they are discovering.

What characteristics does your ideal poem possess?

There is no characteristic. I want it to speak deeply to me, to show me a new view or perspective. Maybe to convict me. I want to be even a bit different after reading and thinking about it. A good poem is always a surprise and a question.

Do you teach poetry? If so, what are you trying to teach through poetry? What has poetry taught you?

I’m a professor of English and creative writing, so I do “teach” poetry. That’s a funny thing as I’m not sure a poem can be taught. It’s a box and it can be opened… in different ways.

On Publishing & Themes Present/Future:

How has publishing your poems changed your writing practice, process, and product?

I hate that word “product.” Publishing is the best way that I know to get one’s work into the hands of others. I love online journals because they may be more accessible to many readers who may not see a print journal (though I love to bury my nose in a print journal and smell and feel the pages). I don’t think that publication (or lack of it) changes me. Sit down. Start in. Write. Hope for the best.

Is there a poem you've always wanted to write but haven’t? If so, why are you waiting? What subjects, themes, forms, aesthetics, etc. do/will you explore in your work?

No, there is no poem I’m waiting to write. As Donovan sang in “Celeste”: “There’s no magic wand/ In a perfumed hand.” I write where I am at the moment. Sometimes I wish I could unearth poems sooner, but they come when they come. I have many poems I’d like to write still. I’m 63. I couldn’t write all the poems I want to write if I lived to be 100. The world never stops giving.

On Oranges:

Oranges or apples? Why?

Oranges. My favorite fruit is a grapefruit (in winter) so I go with citrus. Apples are cool too, provided the skin isn’t too hard. Even more specifically, give me a tangelo.

About the Poet

Kenneth Pobo has a new book of prose poems forthcoming from Clare Songbirds Publishing House. In 2017, Circling Rivers published his ekphrastic collection called Loplop in a Red City. In addition to The Maynard, his work has appeared in: Hawaii Review, Nimrod, Mudfish, Rhino, and elsewhere.