Re- View #8:

My Heart Is a Rose Manhattan

Nikki Reimer, Talonbooks, 2019

&

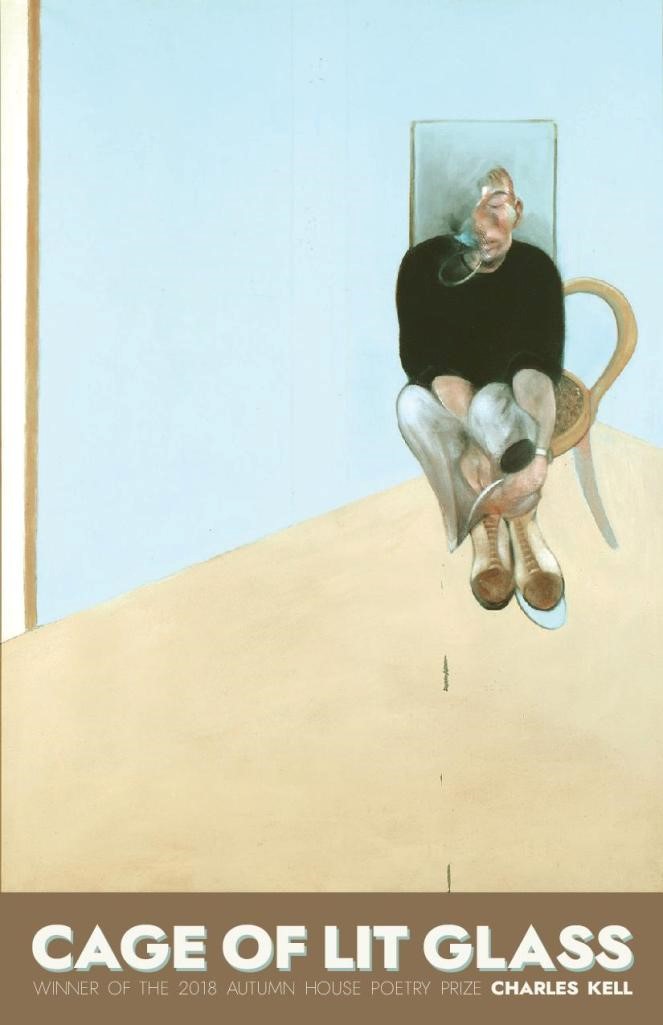

Cage of Lit Glass

Charles Kell, Autumn House Press, 2019

Jami Macarty & Nicholas Hauck, Co-founders & Editors

Welcome to the The Maynard Views Series! Just as Re- View #6 and #7 consist of two conversations about two books, so does Re- View #8 in which we talk about: My Heart Is A Rose Manhattan by Nikki Reimer (Talonbooks, 2019) and Cage of Lit Glass by Charles Kell (Autumn House Press, 2019). Both Nikki Reimer and Charles Kell are former contributors to The Maynard. The title poem of Nikki Reimer’s book, a rose is a rose is a rose manhattan appeared in the Fall 2015 issue. Sophocles and Martin Kippenberger’s Bicycle, two poems by Charles Kell, were published in the Spring 2019 issue.

Jami: I wanted to talk with you about Nikki Reimer’s third book of poetry in part because we selected an earlier version of the multi-sectioned title poem for publication in The Maynard. For me, as an editor, it’s special to follow a poem into its new form and next life in publication.

Nick: I remember Reimer’s poem from that issue. Reading it again, and for the first time in its revised form in the collection, offers me, as its reader new directions, too.

Jami: The title poem announces the book’s unfolding themes, as well as the book’s language and emotional work. The poem’s nine sections offer “my new rose is a work. / this work is grief… my new / grief is a rose” (3).

Nick: This “worker”/ “griever” is someone (the poet), who has “abandoned the city” (4) and who has “ditched leftist civility and set out for the prairies” (5).

Along with the relocation of self within place and politics, there seems to be a relocation that’s on the metaphoric and conceptual side.

Jami: The relocation from city to prairie seems representative of a disengagement with urban capitalism and polis. Along with the relocation of self within place and politics, there seems to be a relocation that’s on the metaphoric and conceptual side. This relocation seems to be the result of dislocation of self—from grief, from sexual abuse, from mental illness. If that’s the case, then the relocation of self is one that takes place during the grieving process and after the reckoning with sexual abuses and other injustices. So, in this opening, we have self and the city; we have the connections between place, identity, and politics. Structures—personal and public, personal and political.

Nick: That helps orient me. Upon first (and subsequent!) reads, I was confused and lost, feeling uncertain about the ground on which I was standing as a reader, the one I took to be offered by the poet and poems. Then the fear of not understanding became part of the reading exercise. I was feeling too witless to say anything about the poems and too engaged not to say something. So, here we are, the review-in-conversation doing what it does best: engaging despite confusion, conferring even through uncertainty.

Jami: I’m not entirely convinced I get it or that my reading is the reading. We’re used to the presence of a prevailing reading, one that makes its subjects explicit and transparent. Our focus on structure and themes belies our reading tendencies and expectations. This collection seems to eschew our typical reading and conferring mode. Perhaps that’s because Reimer’s poems are filled with personal referents, ones that only she and an Reimer insider would understand fully. To some extent, I suppose, that’s true of all poems. It’s just that here that gesture seems underscored, acting as part of the poetics. That seems to have to do with personal griefs shared in the public space of the poems. There also seems to be the expression of a public, cultural grief—over rape culture.

Grief is personal, but we have to do it in public.

Nick: Grief is personal, but we have to do it in public. There’s a tendency to share grief—if that’s even possible—or at least to let it be observed. Does that make grief a performance? I think the poems raise these questions, grapple with them on the page. Sometimes the poems seem to want to let the reader in, but then can’t, or won’t.

Jami: The poems, don’t, I think, willfully withhold. Rather, the specifics stay personal, but they’re extrapolated and applied to the general—public, city, politics, culture. For instance, the CanLit references—one would have had to have had firsthand experience to understand the references fully. The abuses of power, the injustices affected many, but some were closer to the central infractions.

Nick: As we’ve sought to get thematically situated within the poems, you touched on structure and form. There are a variety of poetic forms and devices being used. Reimer seems to test form, which, while multifarious, remains structured.

Jami: I am thinking of the ways work, grief, and (gendered) identity are structures, the way city and prairie are structures, the way politics and culture are structures. That is, the way humans are reliant on structure, the way our system of communication is a structure and is reliant on structural conventions. Of course in this context, the way creative expression and reader engagement is reliant on structure. Structures of these types are questioned in Reimer’s poems.

Nick: Structure, structure, structure. Repetition is a prominent structural element within the collection. I’m interested in the ways repetition relates to the themes being explored. For instance, the poem “That winter” (86-89), uses the rhetoric device anaphora:

that winter sometimes suffering from whiteness…

that was the winter after the winter we found his body…

that winter I tried to perform erasure on this manuscript…

that winter don’t even try to subvert the lyric subject…

that winter I was either in or out or in and out of control…

Jami: Repetition and form (structure) are foregrounded in the series of epistolary poems that make up the collection’s third section: “letters to the ethernet.” Here, we connect to an aspect of the public, a new type of city, offering a new aspect to our culture—the Internet. This series of poems connects the epistolary with its Biblical and 13th century literary references to Web technology. Talk about contemporary poetics! Take this from “Dear LinkedIn”:

I want it all:

market manipulation

constant instant continual contact

aspirational achievement

forced flexion

omnibus omnipresence (35)

Nick: There are also instances of morphological progressions of individual words and sentence fragments, like the end of “Our sorrow is normative,” for example:

and thus is hipster-normcore

hipstercore, if you will

or normster

or nipster

but not napster

that word has most definitely jumped the shark (66)

Jami: And, instances of aural progression via vowel/ assonance. When I read/ hear the title and the title poem’s “rose,” somehow my ears progress to “woke.” Of course, I also hear Gertrude Stein’s infamous expression of the law of identity: "A rose is a rose is a rose."

Nick: I think the way language is used says something about grief and how it’s never really overcome. To come back to “Our sorrow is normative”:

and our grief will at some point if it has not already

approach the grotesque

which is the farthest thing from normative

or alternately the normcoriest affect imaginable (64)

The formal variety in the collection is saying something about the language of mourning.

Jami: The formal variety in the collection is saying something about the language of mourning. But also the language of all structures. Language is a structure and it creates, adds structure. So, the commentary is both on the thing and the medium used to describe or express the thing—the law of identity. It goes back to referents—personal/ public, personal/ cultural, city/ prairie, etc. And, to the reflexive, referents to self and text, what I call the textually reflexive.

Nick: Writing poetry, publishing poetry, and poets come up throughout the collection. The Stein reference is situated somewhere along the book’s private/ public continuum, it just happens to be more accessible—to readers of literature anyway. The collection’s epigraph from Erin Mouré’s Furious (1988) orients readers to what is forgotten and remembered, and the ability or not to express it. It’s an apt opening.

Jami: The Mouré epigraph seems to be a comment on grief—the expression of grief, but also the silencing, oppression, and repression that can take place in situations of abuse of power and sexual misconduct: “do you feel implicated / does it make you uncomfortable.” It’s also about writing itself—what is writing, if it’s not seeking to express what we remember, what we don’t want to forget, what we’re haunted by, and what is hard to express? What is writing if it is not to stave off silence? If not to resist being silenced by self or other?

I don’t know why bodies are so perilously fragile

yet I trust the sanity of my vessel

and we’re still here, aren’t we?

hearts pumping, lungs flapping, blood thronging in tiny rivulets under the skin

still here, trying to divorce ourselves from #canlit

(“Meditations in an emergency,” 84)

Nick: This also speaks to place, location, attempting to express what is repressed by certain situated, local circumstances. Both Reimer and Mouré call Calgary home, and much of the politics in Rose Is a Rose Is a Rose Manhattan is directed toward Western Canadian, specifically Calgarian/ Albertan, conservative values, where “out here it’s important to know oil / to grow, to blow oil” (“alberta,” 29). This poem also ridicules expressions of masculinity: “out here it’s important to know how to barbeque / else how will we know you are a man?” (29).

Jami: And yet the very first word of this collection is “apolitical!” (3). And later, there’s the consideration of what to do “when every poem has bad politics” (23).

Reimer’s work is political but it refuses to waste too much time getting weighed down by Politics.

Nick: Reimer’s work is political but it refuses to waste too much time getting weighed down by Politics. It’s as if engaging on politics’ terms and in its language structure would be a concession. It took me a while to make sense of the political angle in the poems, and I’m still not sure I’m clear on it. I feel that there’s something else, more intimate and more important, being said beyond “the literary industrial complex” (30).

Jami: I see politics as another structure under examination within the poems. The poems seem to ask what is political? What personal? When does one supersede the other? The poems ask whether or not poems are political or should be. And, perhaps more pointedly, the poet takes on the question: what can poems do or change?:

my work will not create new imaginative

worlds to help guide the way

out from the ruins of late capitalism. my new politic

will not soothe the wounds of empire. (3)

Nick: Late in the collection, Reimer references Frank O’Hara. Reimer’s poem “Meditations in an emergency,” asks “where’s Frank O’Hara when we need him?” (84). So, is it language’s emergency? Poetry’s?

Jami: All of the above. All cultural structures are dislocated and being relocated. So, why wouldn’t artistic structure and culture be included? These questions are particularly poignant when poets and poems are the targets of abuse of power and injustice.

Nick: That brings us to: “Trigger warning” (77-81), written as a script for four voices:

VOICE 1: I heard he raped her

VOICE 2: I was told he raped her

VOICE 3: She told me he raped her

VOICE 4: She told me he threatened her with libel if she told anyone her raped her (77)

Jami: Chilling, revealing of how quickly discourse, especially around rape, becomes depersonalized and distorted. The lines also speak to the shifting nature of accountability and normalization of abuses of power within institutions. It’s worth reiterating that not only is Reimer questioning the personal and the political, but also the personal and the cultural. The culture of power structures within academia and CanLit. Rape culture within CanLit, academia, and society.

Nick: The four voices gossip and throw out the lines: “He has received many awards” (80), “He is an important writer” (80), and “He is a pillar of the community” (81), echoing media’s and society’s vapid debates.

Jami: As if accolades are mutually exclusive from abuse of power. Also, this is the way conversations that are about behavior turn toward the validity of accusation—in other words, the way the validity of the victim is questioned because of the reputation of the perpetrator: “He is an important teacher / He is an important writer (“Trigger Warning,” 80).

Nick: Reimer’s work is interesting because of the way that she engages with current issues without succumbing to the familiar tropes. The poems call-out of the abuse of power within institutions is never lost in the formal acrobatics. Humour helps. Instead of dismissing or appeasing, as humour sometimes does, Reimer offers it as an irrevocable part of her call-out poetics:

if your feminism tries to be intersectional but falls apart

at the conifer of grit and hipster radio—

maybe try not to be such a motherloving effervescent dick about it?

(“alberta,” 25)

Jami: Here, we have the coincidence of Rape Culture and Call-out Culture! Back to “Trigger Warning” (80): “And many of us did not know that men in our circle / are rapists.” This raises questions of who’s protected, who safe? No one. Nothing. Even grief, intimately and intensely explored in other poems, gets a turn:

i’m very sorry for your loss

do you still wear progressives? (58)

Nick: And, back to “Our sorrow is normative,” where not even the poet is spared: “capitalism might be late, but my period she is right on time” (65). There’s a stinging charm to Reimer’s wit that only a poet with a developed and thoughtful self-awareness can pull off, a poet who may have reached “peak self,” as in “I feel like I’ve reached peak Nikki Reimer”: “You can tell I’m the poem’s speaker because I can’t stop swallowing / the line endings” (85).

Jami: Humor may be the most transgressive act there is—in art and in life. How does the saying go: women are afraid men will hurt them; men are afraid women will laugh at them. The one laughing is not the one crying, and in some ways to be laughing is to be in power.

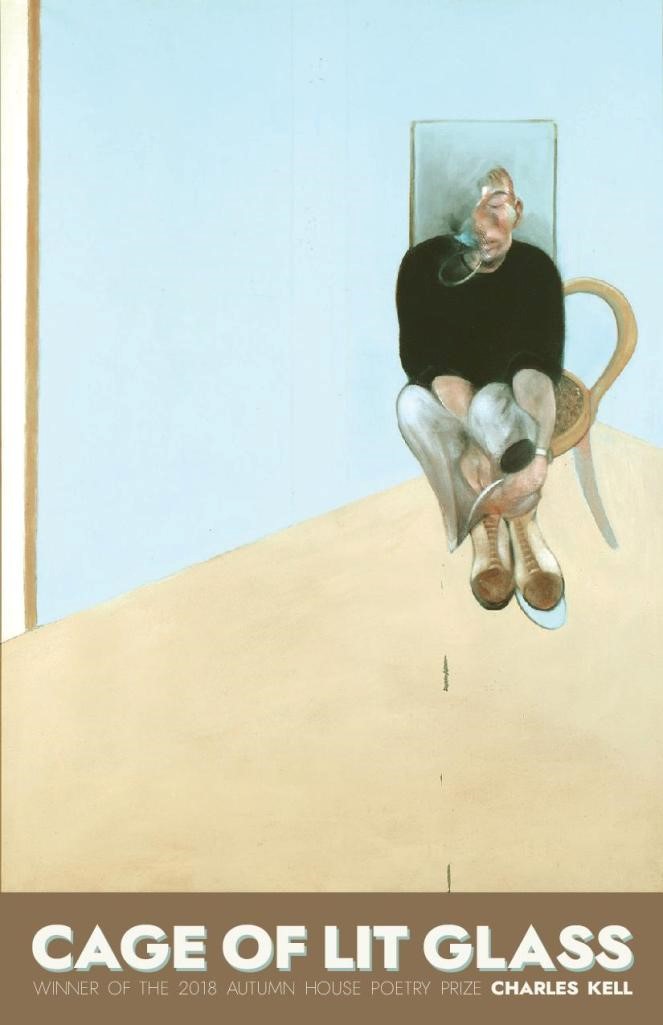

There’s more to say about Reimer’s provocative collection, of course, but time and word count compel us to turn our attention to Charles Kell’s debut collection, Cage of Lit Glass, which won the 2018 Autumn House Poetry Prize.

Guilt is one of the cages within the work.

Since reading the collection for the first time, I’ve been thinking of the book as an exploration and expression of guilt. Guilt is one of the cages within the work. There are other psychological cages within the poems and there are also physical cages that take the form of jail cells and in-patient treatment centers, as we learn in the first poem, “In the Penal Colony”: “A traveler / / might wander down the wrong / road and end up here” (2).

Nick: In the first poem, there’s an attempt to shut out the world with “wax to plug my ears against / the din,” showing the traveler “how to put the wax in” (2). Is this a reaction to guilt? A way of learning to live with(in) cages? As the John Ashbery epigraph to the first section suggests, “We must learn to read / In the dark.”

Jami: Taking cues from the title of the book’s first of four sections, the reader is to first focus on “enclosures.” From the opening poem, the reader begins to know the sort of enclosures being referred to where “The walls / either move or sit still” (“Rimbaud,”4), where

There is a phenomenon amongst

former prisoners where after release

they begin to construct the very

dimensions of the cell they once

were housed in. (“Cenotaph,” 5)

Nick: This “phenomenon” also caught my attention. It expresses the difficulty of escaping habitual behaviours. Structurally, the book points to this theme in recurring poem titles: “In a Dark Room” (10 and 65), “Lincoln Town Car” (15 and 41), “Vetiver” (18 and 70), and “Felon” (45 and 62). Then, there are the three poems entitled “Self-Portrait” (13, 43, and 66).

Jami: The series of paired poems and the three “portrait” poems along with the cover image, featuring Francis Bacon’s “Study for Self-Portrait, 1982” have me thinking of walls—two sides, four sides—the dimensions of a room or cell, where “I was trapped in Lorain, Ohio, wearing / an issued blue uniform (“Rimbaud,” 4).

Nick: I think the self, and identity, are also being explored as forms of enclosure.

Jami: If Reimer’s central reality and metaphor is dis/relocation, Kell’s is confinement. As well as the confinements associated with the judicial and penal systems, there is the confinement of death: “trapped / in one last spot” (“Mark’s Death Mask,” 6). Those associated with sexuality: “I can become something else” (“Bodybuilder,” 7). The trappings of addiction: “On day seven I think of the people I have hurt” (“Two Weeks Inside a Locked Attic,” 9). Those associated with self-judgment: There’s “[t]he sickness over / what we’ve done to our lives” (“Lincoln Town Car,” 15). The “manifestation of my mens rea” (“Enclosures,” 17), the knowledge of wrongdoing that constitutes part of the crime.

We discover or create new enclosures when free, we learn to be free when enclosed.

Nick: If there’s a play between confinement and whatever it’s opposite would be—freedom?—the binary is muddled. We discover or create new enclosures when free, we learn to be free when enclosed. In the poems, binaries surrounding sexuality and guilt are porous as well. In “Lincoln Town Car,” there’s “our kiss which / was over in a second & never // mentioned again” (15) and in “Guilty”: “I couldn’t say if I loved you when you / held me down” (40).

Jami: The guilt seems to be connected to homoeroticism. The guilt also seems to be connected to “Mark’s death.” This is survivor’s guilt. This is “Destruction in the present tense—accident” (“Mark’s Death Mask,” 6). “Empty Specter” (8), a villanelle, with its two lines of refrain, enacts both the trauma and the circular after-thought that occurs when a person believes they have done something wrong by surviving a traumatic event: “making me want to scream but my mouth fills with glass.” Here, the traumatic event has to do with “[a] fifth of Maker’s Mark and some blow,” which results in a “mausoleumed Jeep Cherokee” and “Mark’s body, lying for the last / time next to me.”

Nick: The attraction and guilt seem to be interwoven somehow, nothing here is straightforward: “It’s silly to call time a linear / palimpsest (“In a Dark Room,” 11). This brings me to how the overall structure of the book and the poems conjure mirrors, copies, Doppelgängers. These are mechanisms of self-examination, as well as imagined forms of possible escape. The poems seem to suggest that self-examination and escape are inseparable.

Jami: Mechanisms of self-examination and also signifiers of two sides. Are things what they are or a reflection/ a copy of what they are? Hiding and invisibility, as in the poem titles: “Self-Portrait as Invisible Being” and “Janitor Hiding in a Locked Closet” factor within the poems: “Or else you couldn’t see me if / you tried” (“Self-Portrait as Invisible Being,” 13)

Nick: It’s “a copy of a copy of no copy”; duality is confirmed and denied, “both a part and / apart” (“Enclosures,” 17).

Jami: The second section, or, wait. Now, I want to refer to it as the second wall of this room, this cell of poems, entitled, In a Field, uses another physical space to speak of confinements that come from memory and its returns and repetitions:

Two Fields

1.

In a strange field never

entered. Here once, though

I can’t remember when.

2.

In a strange field never

entered. Here once, though

I can’t remember when. (24)

This poem enacts mirroring, replication, and it also enacts disorientation and remorse.

Nick: I’m trying to make sense of the “phantom beat between two rhythms” in the Rosmarie Waldrop epigraph which introduces this second section. Gilles Deleuze suggests that three pictorial elements can be seen in Bacon’s work: fields (large, spatializing material structure), figures, and place, the common limit between figure and field, where there is no narrative, but where something is happening, which defines the functioning of the paintings. Could this be a way of approaching Kell’s work?

Jami: I’m aware that I am trying to assemble the poems into a narrative. The poems seem both to invite and eschew narrative. Sometimes it feels like the referents within the poems are literal. Other times, they are surreal. Of course, both can be true. And, maybe there are more than two views being presented here. “Views” seems particularly apt when describing these poems, each of which is portraiture.

Nick: Yes, I sense that the literary and artistic references support this. This section’s longer, five-section poem “The Lost Boy,” speaks to genre: film, novels, memoir, painting. The cult-vampire film The Lost Boys is referenced here, as is Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo, a novel that, after doing a bit of research, I learned was a major influence for Magical Realism. The poem also references bildungsroman. Is there a narrative, here, or an anti-narrative?

Jami: These poems trace a descent. There is interest in supernatural forces, but it’s “sciosophy,” so pretend: “I can never imagine what it’s like not / to want.” If these poems are in AA, then they’re having a hard time accepting Step 3: “Let go and Let God.”

Nick: Nice connection. Substance misuse comes up often in these poems, and I get the sense that there’s no real escape here either. We’re back in Bacon’s field and figure.

Jami: In this second section, it snows a lot; ice hardens over. This has me thinking about scabbed-over wounds. In these poems, there seems to be a covering, a hardness, something impenetrable, or inescapable: “You don’t really know / what is happening” “(Welcome Snow,” 26). Of course, this also speaks to other shapes and forms of enclosures and confinements.

Nick: I take these recurring topoi as part of an exploration of confinement—enclosed thematic spaces and objects: snow, cars, bourbon.

Jami: The collection’s third section/ third wall, Exculpation, offers ascent, associated with forgiveness. In this section, self is, to some extent, forgiven. Others, too, seem to be forgiven. That’s revealed in the asking of release and relief for others, as in “Please Free My Dear Friend Jack” (48). Here, in this section, the poems get close to prayer and compassion for self and other.

Nick: Structurally and thematically, I think sections one and three work together (as do sections two and four). Exculpation responds to Enclosures, but with poem titles like “Repeat Offender” and lines like “I swore this would all change” (“In a Dark Room,” 65), I don’t feel there’s any release or resolution.

It’s as if sections one and three form two of the facing walls within the book’s room/ cell, and sections two and four form the other two.

Jami: I’m with you. It’s as if sections one and three form two of the facing walls within the book’s room/ cell, and sections two and four form the other two. This metaphor is one way I’m coming to understand how the structure of the book and the form of the poems contribute to the content. Is this intentional on the poet’s part? I’m not sure, but of course we readers are doing our thing, bringing our own intentions to the poems.

Nick: If it is the intention of the poet, it feels a bit heavy-handed, which, I guess, heightens the theme of confinement.

Jami: In this third section, there’s also a revisiting of friends and family, where “[c]ontemporary preoccupations rearrange / past events” (Nineteenth-Century American Literature,” 51). This section seems focused on making amends, which is among the 12 steps of AA. These poems seem involved in letting go, and gaining objectivity and perspective: “At last, he can say, wrong” (“Exculpate,” 57). If the first section reckons with the past, and the second section refers to consequences of the past, then this section is perhaps about nexts—what now? Who now?

Nick: I sense this movement as well. I wanted to say “progression,” but I’m reluctant to use the word. The mother in these poems seems to complicate progress. “In a Dark Room,” “she has been drinking for days” and “both of us almost the same” (65). Is she “My Alcoholic Other” (73)?

Jami: The poems deal directly with self and family, and the heredity nature of alcoholism/ substance abuse, leading to a death of one sort or the other. At this point, recurring images are starting to bunch up around me. Particularly in this section, cemeteries—“small cemetery / in Footville, Ohio” and “Father’s Small Box” and cars—“Town Car,” “Pontiac,” recur. Both of these are confines/ ing, and both can be graves.

Nick: At first these tropes—cars, bourbon—seemed part of an imagined “man-cave” (another enclosed space) but now I’m not so sure. Here, repetition reiterates and dismantles, like habit struggling to rid itself of itself.

Jami: Speaking of recurring images and concepts, foretelling, “haruspication” factor. And, is it just me or is there a lot of shaving in these poems? Is this an expression of the masculine or…? What is it to be cleanly shaven? Is this another metaphor for the removal of what’s unwanted? My mind seems to want to get at the incidence of shaving. Under what circumstances is the hair removed and by whom? Hair removal is treated as a choice, for aesthetics, and is erotic within the poems. In “Bodybuilder”:

He takes a fresh razor

presses gently to his chest

staring dead-straight in the mirror.

Cock in left hand…

I wonder about when hair removal is not a choice. For instance, a prisoner’s hair is cut before entering prison.

I think the shaving references could also be suggestive of transforming the body, removing identity/ identifying features.

Nick: These references could be particularly masculine. Hair is cut also when men join the army. I think the shaving references could also be suggestive of transforming the body, removing identity/ identifying features. Maybe it’s suggestive of androgyny, shaving off gendered dualisms and cultural signifiers.

Jami: So, it fits that an old self is being removed, exfoliated. The book then acts like an elegy for self, the type of man that self was. The book’s also most certainly an elegy for the man Mark, the dear friend killed in the car accident. Btw, late in the book when Marc with a ‘c’ is introduced, I had a moment of confusion.

Nick: The two “Mark/c/s” threw me off, too. “Marc” seems to be family, whereas “Mark” is childhood friend, attraction, tragedy. Or is memory warping illusions?

Jami: In the end, both the book’s and life’s, there’s a release from even the prison of illusion: “I thought / everything would one day / get better after all of our prisons” (“Daguerreotype,” 72).

Nick: There’s a curious play on presence in the poem: “Here is this photo I’m holding // now…never letting go” (72).

Jami: A photographic process used in early photography, a daguerreotype is, here in these poems, another type of portrait and a type of “trapped.”

Nick: The book’s final poem, “Far Village” seems, at first, to be conciliatory with the self, with enclosure, and with the past: “I am seeing things. / Figuring things out.” However, temporal and spatial realities are denied value: “I could tell you in past & present / tense” that “[t]he world is nothing,” is empty space where “[w]e sit…waiting” (83).

Jami: This requiem is false. The poems simply “List things, excavate spaces” (“False Requiem,” 78). As the penultimate poem title says, we are all just “Reading in the Dark” with a “back against the metal bowl // The sound of men banging on bars” (82).