Inter-

Laura Cesarco Eglin

On Practice:

Do you write at the same time every day, in the same place? How would you describe your writing practice/s?

I am intentional about carving space for reading, which is an essential part of my practice, and writing: it can be in the morning, at night, in the middle of the day.

What do you do if you get stuck while writing a poem?

I leave it resting on the page. Go on with the day, and with no pressure, I come back to it later.

Sometimes it’s the next day, sometimes it’s a week later.

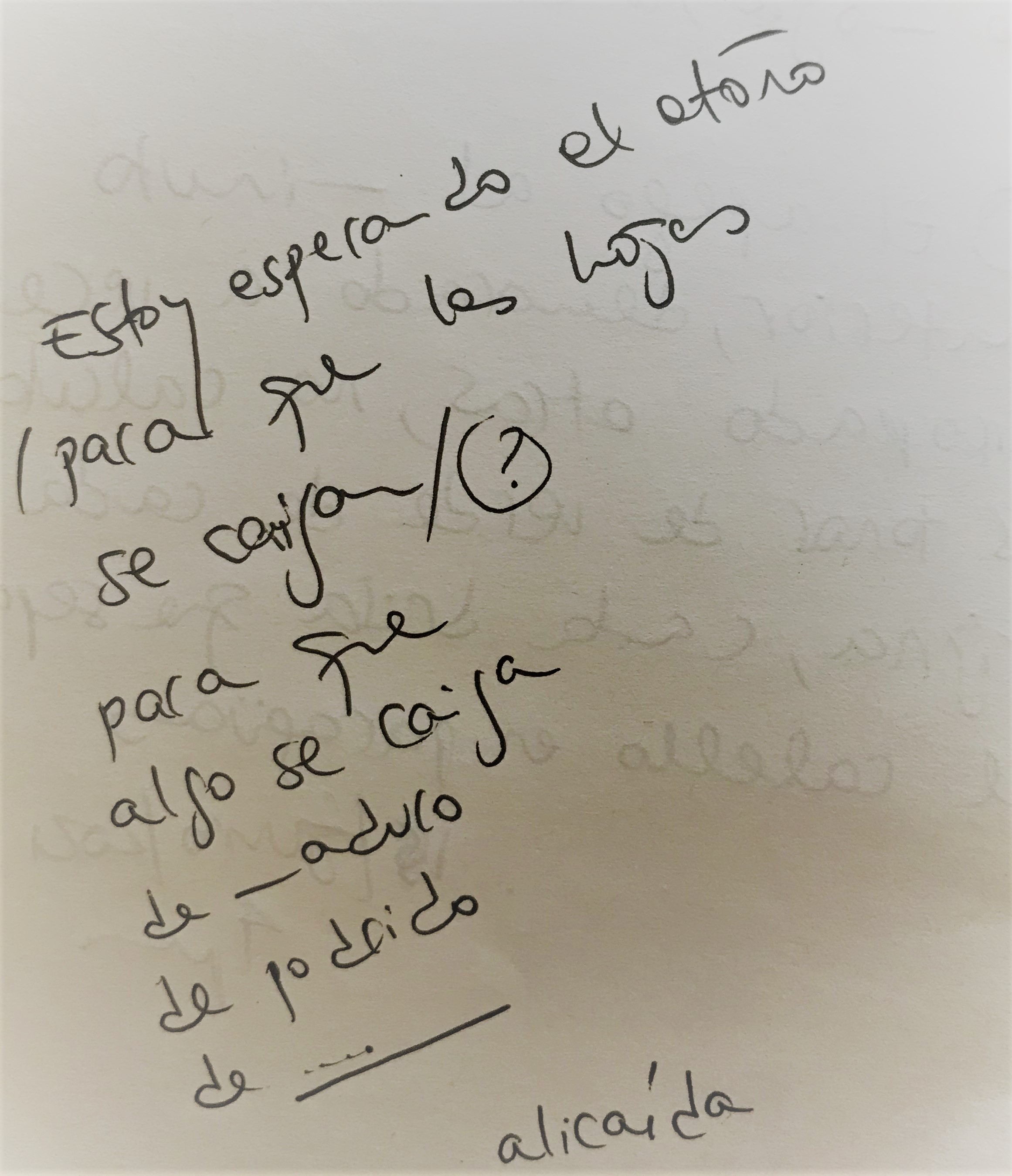

Take a photograph of a page from your notebook or a screenshot of an electronic file of a poem you have been recently writing or revising.

On Poetry:

Is there something you once believed about poetry that you no longer hold true? What changed?

I believed that poetry remained on the page.

But poetry is much more than that; it’s a way of participating in the conversations about what’s important.

Poetry is a modus vivendi.

What can/does poetry change?

Poetry is very powerful.

It can change the way we perceive something, it can change the way we relate to language, and the choices we make; it challenges the status quo.

Is there something you now think you know about poetry that you wish you’d known a decade ago?

I learn about and from poetry constantly.

It’s natural that what I know now I didn’t know a decade ago.

On Influence & Inspiration:

What books are on your night stand, the back of the toilet, your desk?

What I have on my night stand changes, depending on what I’m reading or rereading.

Right now there’s From a Winter Notebook, by Matvei Yankelevich; the proofs of Veliz Books’ forthcoming poetry book Share the Wealth, by Maureen Thorson; Night Sky with Exit Wounds by Ocean Vuong (I’m teaching this book this semester), and Awaiting Major Events — Espero grandes acontecimientos, by Nurit Kasztelan, translated by Maureen Shaughnessy.

Which writer/s do you (re)read the most? What does the writing do for you upon return?

I mostly read contemporary poets, either in a language I know or in translation.

I return to many poetry books. Sometimes I reread them from cover to cover and, sometimes, I return to certain poems within the books.

Rereading and returning, is reconnecting, (re)discovering, learning.

Among the poets you most admire, who has influenced you the least? Why have you not been influenced by his/her work?

It’s very hard to rank influences in this way. Everything I read influences me because reading helps me learn to find my voice, to try new things, to see what resonates with me more and what doesn’t.

Reading others’ work opens possibilities of writing, or worlds.

Describe a moment from your life when you've been overcome by how beautiful something is.

Being moved by something and finding beauty is something that happens daily.

It’s being open to feeling.

Poetry.

On Teaching:

How would you describe poetry to a four-year-old? To the non-literary family ancestor you imagine as a great source of who you are?

I didn’t have to describe poetry to my grandfather. He already understood that we were both poets. This happened while talking about my second book of poems, Sastrería/Tailor Shop (Yaugurú, 2013), whose central theme is memory.

Memory works in the same way that both a tailor and a poet do. They use fragments, snippets as a starting point—signifying and resignifying the pieces of the past to create a present. Sastrería/Tailor Shop explores the different negotiations we participate in through memory and about memory: repetitions that are never exact copies of the original experience; cancer, as something that is remembered in the body from generation to generation; what is inherited as the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, etc. Sastrería/Tailor Shop speaks of a memory that is alive and vibrant, for it is active in revitalizing a past, in sewing a present.

My grandfather understood this as well. A few months after Sastrería/Tailor Shop was published I went to Uruguay. He and I were sitting on my mother’s balcony and talking about my book. At some point he made a comment that sounded very poetic and he recognized that. He smiled and said: “See? I’m a poet too.”

What characteristics does your ideal poem possess?

It’s a poem that observes deeply, thinks profoundly, and associates intuitively.

Do you teach poetry? If so, what are you trying to teach through poetry? What has poetry taught you?

Poetry has taught me to observe, to question, to be vocal, to be responsible with language, to imagine, to think.

When I teach poetry, I try to show my students how powerful poetry is.

On Publishing & Themes Present/Future:

How has publishing your poems changed your writing practice, process, and product?

It hasn’t.

Publishing has to do with sharing, with being part of communities; it’s being in dialog with other poets, writers, translators.

Is there a poem you've always wanted to write but haven’t? If so, why are you waiting?

I don’t have a plan.

What subjects, themes, forms, aesthetics, etc. do/will you explore in your work?

Writing is exploring.

On Oranges:

Oranges or apples? Why?

Oranges, because, as I say in my poem “Say It Delicious” (published in The Maynard Fall 2021):

“I’ve assigned magic to oranges

the belief that anything can be

improved with its juice or rind”

About the Poet

Laura Cesarco Eglin is a Uruguayan poet and translator (from the Spanish, Portuguese, Portuñol, and Galician). Her latest poetry collection is Life, One Not Attached to Conditionals (Thirty West Publishing House, 2020). Cesarco Eglin’s translation of Hilda Hilst’s Of Death. Minimal Odes (co.im.press, 2018) won the 2019 Best Translated Book Award. She’s the publisher of Veliz Books and teaches at the University of Houston-Downtown.

Inter-

Derek Thomas Dew

On Practice:

Do you write at the same time every day, in the same place? How would you describe your writing practice/s?

As of late I read as early in the morning as possible and begin writing in the early evening. I need the day for gestation. Always in the living room. When I sit down to write, cross legged on the floor, I blast music, rage through it, bang my head against the wall, lip sync drums, etc. It’s inwardly hectic. I find it helpful to be pulled in several directions at once. I like the sound of a DJ scratching. About his marksmanship, the Sundance Kid said, “I’m better when I move.”

What do you do if you get stuck while writing a poem?

Stare into blank space. Take a walk around the block to reacquaint myself with air and the way the world crawls through it. Take note of words in advertisements and matchbooks and anywhere. Skateboard or watch skateboard videos. Meditate on the similarities between matter and motion, how neither can be destroyed, all the ways we relay them to their next lives.

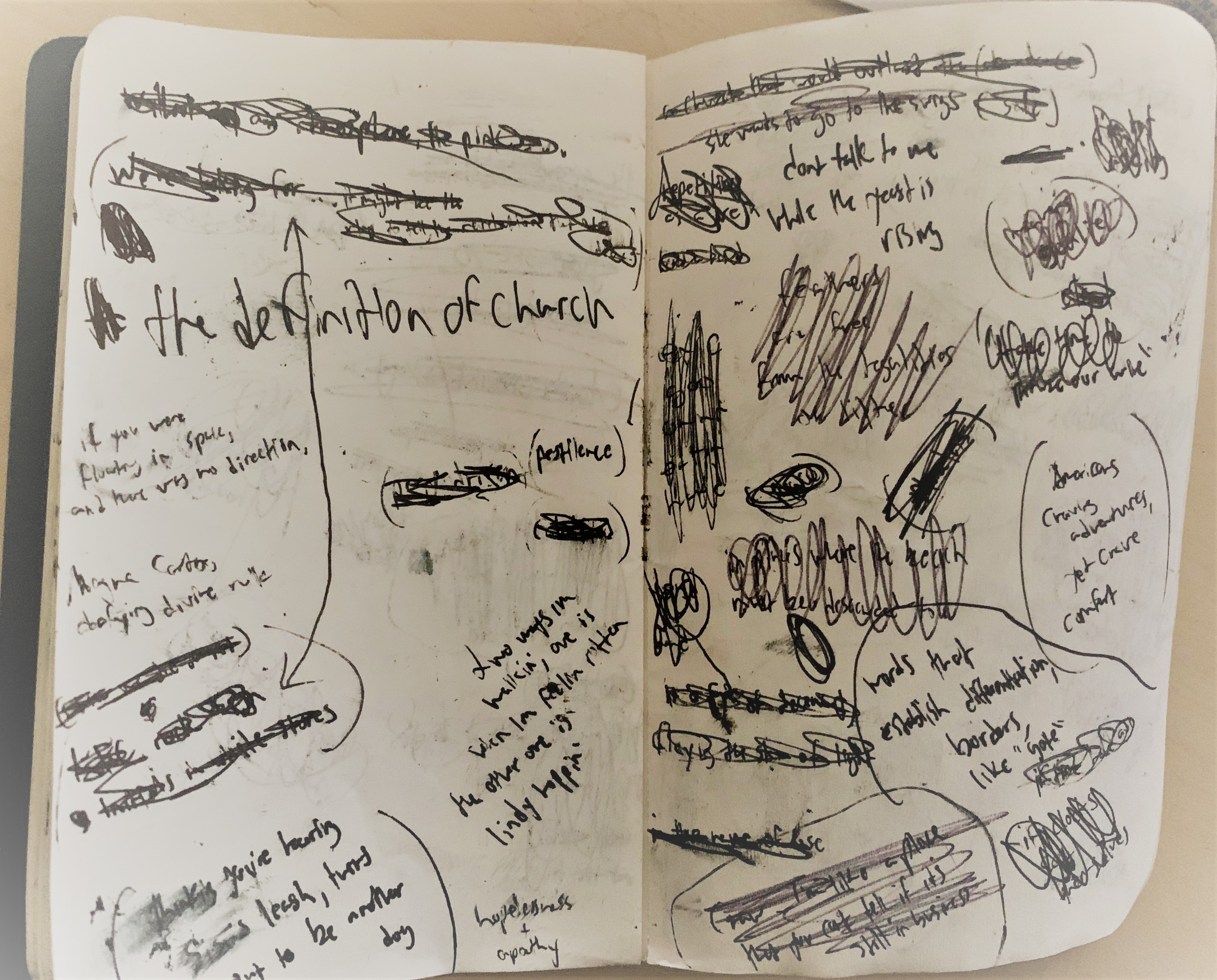

Take a photograph of a page from your notebook or a screenshot of an electronic file of a poem you have been recently writing or revising.

On Poetry:

Is there something you once believed about poetry that you no longer hold true? What changed?

I’ve never really held solid convictions regarding poetry, except that it’s one of the few things that’s got me convinced. Of what, I don’t know. But I’m convinced.

I realized at some point that my act of building had lost the act of expressing. And, having spent the earlier part of my life telling everyone to get lost, I felt it was time for connection.

I once wanted everything to be a slash, the anti-refined. I learned to soften that.

What can/does poetry change?

Poetry suggests the elsewhere that we belong to. Poets do the work of fungi, swallowing and redirecting vitality, revealing subterranean networks.

In list form, no particular order:

The compulsion leads to defamiliarization and, ultimately, reconfiguration.

The compulsion changes the bioelectricity in the lungs.

The compulsion shocks one into regeneration of soul and limb.

The compulsion teaches one how to be a better human being, to empathize.

The compulsion helps cultivate an appreciation for the non-utilitarian, for the just is.

Is there something you now think you know about poetry that you wish you’d known a decade ago?

In the beginning it was about silence, then what I was thinking, and later what I was feeling. As I went on, thinking and feeling somehow learned to harmonize their articulations in silence while I waited for something to possess me and it furthered the urge.

I learned the brighter epiphany is usually the one prepared for, not foraged for, and that just consistently showing up to throw darts is likely to result in excavating a premier bullseye.

On Influence & Inspiration:

What books are on your night stand, the back of the toilet, your desk?

Susan Howe to offset Dante, Donald Revell to accent Rilke.

Ralph Angel in conversation with Michelle Mitchell-Foust.

Which writer/s do you (re)read the most? What does the writing do for you upon return?

Caesar Vallejo and Paul Celan have this way of waking up inside a poem which refreshes me. It’s like smelling salts. Gertrude Stein and Rae Armantrout get me thinking about language.

Among the poets you most admire, who has influenced you the least? Why have you not been influenced by his/her work?

Phillip Levine and James Tate are good candidates. I love their stuff, but am never inclined to do what they do.

Describe a moment from your life when you've been overcome by how beautiful something is.

It’s an everyday deal. It’s usually people. If you think you hate someone, just imagine their morning bathroom routine, the putting on of their shoes.

When I was fourteen, I was walking through an alley to my friend Jonathan’s place. A little old lady was walking in front of me. It was a summer Saturday. Southern California asphalt. Along a splintering fence in disrepair. Totally silent. Daisies on her jacket. I was spellbound by her slow yet supremely confident pace and gait. I walked right past Jonathan’s door. When I realized nothing permanent needed me, I felt like I could talk about everything.

On Teaching:

How would you describe poetry to a four-year-old? To the non-literary family ancestor you imagine as a great source of who you are?

To the four-year-old, I’d quote Osip Mandelstam: “There’s fuel enough to forget the weather”

To the non-literary family ancestor, I’d quote Octavio Paz:

“Headlights drill quick tunnels

collapsed in a moment”

For the four-year-old, I’d add that retinal retention can be exploited for the sake of sleight of hand, replacing the image replacing the image.

For the non-literary family ancestor, I’d add that the sculpture need not inform beyond its own living form.

What characteristics does your ideal poem possess?

Authenticity.

An orchestrated unpredictability that never falls prey to its own paroxysms.

Brevity.

Do you teach poetry? If so, what are you trying to teach through poetry? What has poetry taught you?

When I begin teaching poetry, I’ll try to get folks to consider tattoos, the messages scrawled on bathroom stalls, the graffiti in public spaces. The pages of a book or limbo of an anthology can degenerate into private real estate forbidding a certain physicality that might be crucial these days. There’s something for any and every attention span. It might help to emphasize poetry as the means and the world as the end, rather than vice versa.

When we were born, there were different objects under different weather than are here now, different angles and light, but, also, a frozen reaction to a primordial language of emotion presented in it all. Poetry taught me we’re the friction between old and new. It taught me that when you sit down to order food at a restaurant, whether or not you’re the same person when the food arrives depends on if you can remember the last thing you ate.

On Publishing & Themes Present/Future:

How has publishing your poems changed your writing practice, process, and product?

I found out that I can dress my children up for school, but can never know which outfits will get them beaten down and which will get them complimented. It’s okay. When I receive a rejection, I don’t stop to consider why. Everything can’t work everywhere.

Is there a poem you've always wanted to write but haven’t? If so, why are you waiting?

The one that gets it right? I’m not waiting. Lately I’ve been concerned with an elder I see at my favorite deli holding a Grubhub bag.

What subjects, themes, forms, aesthetics, etc. do/will you explore in your work?

What loss means in an age when connection means I don’t know what.

On Oranges:

Oranges or apples? Why?

Oranges, because of the peeling.

About the Poet

Derek Thomas Dew’s debut collection of poetry, Riddle Field (University of Nevada Press, 2020), received the 2019 Test Site Poetry Prize. His poetry has been published in a variety of journals and anthologies, including Interim, Twyckenham Notes, The Maynard, The Curator, Two Hawks Quarterly, Tempered Runes Press, Cathexis Northwest Press, and elsewhere. He’s a winner of an Oregon Opportunity Grant and Omnidawn Publishing Workshop Scholarship.